Initiële behandeling bij volwassenen met epilepsie

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de initiële behandeling van een gegeneraliseerde convulsieve status epilepticus bij volwassenen?

Aanbeveling

Indien een intraveneuze toegangsweg beschikbaar is, gebruik bij voorkeur intraveneus lorazepam of intraveneus midazolam als initiële behandeling bij gegeneraliseerde convulsieve status epilepticus bij volwassenen.

Indien geen intraveneuze toegangsweg beschikbaar is, gebruik dan bij voorkeur midazolam nasaalintramusculair.

Gebruik intraveneus fenytoïne, intraveneus levetiracetam of intraveneus valproaat om een voortdurende convulsieve status epilepticus te couperen.

Volg het stroomschema, zie bijlage.

Overwegingen

In de literatuur analyse is gekeken naar de behandeling bij een gegeneraliseerde convulsieve status epilepticus bij volwassenen, hierbij werden vijf studies (waarvan twee systematic reviews, drie RCTs) gevonden. Een breed scala aan medicijnen worden in deze studies met elkaar vergeleken (bijvoorbeeld diazepam, lorazepam, fenytoïne, valproaat, levetiracetam). De studiepopulaties in de gevonden studies zijn relatief klein, met enkele methodologische beperkingen (risk of bias, inconsistentie, imprecisie). De bewijskracht van de literatuur is daardoor zeer laag voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat seizure cessation en zeer laag voor de cruciale uitkomstmaat termination of SE after drug administration. Dit betekent dat nieuwe studies kunnen leiden tot nieuwe inzichten. Derhalve kunnen er op basis van de literatuur geen sterke conclusies worden getrokken over welk middel het meest effectief is en de voorkeur heeft bij de initiële behandeling bij een gegeneraliseerde convulsieve status epilepticus bij volwassenen. Opsommingen van middelen in onderstaande tekst staan op alfabetische volgorde.

Eerstelijns behandeling

Bij de behandeling van een status epilepticus bestaat de eerstelijns behandeling uit een benzodiazepine. Zowel uit oudere als recente gerandomiseerde studies komt naar voren dat benzodiazepines effectiever zijn dan placebo in terminatie van een epileptische aanval (Alldredge, 2001; Spencer, 2020). Midazolam, lorazepam en diazepam zijn de meest onderzochte benzodiazepines, waarbij diverse toedieningsvormen onderzocht zijn. Diazepam intraveneus lijkt minder effectief dan lorazepam intraveneus (Kobata, 2020). In het geval dat er nog geen intraveneuze toegang is, heeft midazolam intramusculair de voorkeur boven lorazepam intraveneus, aangezien onnodig veel tijd verloren gaat aan het verkrijgen van een intraveneuze toegang (Silbergleit, 2012). Als een intraveneuze toegang wel beschikbaar is, kan gekozen worden voor midazolam of lorazepam. Relevant direct vergelijkend onderzoek tussen deze twee benzodiazepines ontbreekt, maar het is niet heel waarschijnlijk dat die middelen op klinische relevante wijze verschillen in effectiviteit bij de behandeling van een status epilepticus. Derhalve beschouwt de werkgroep midazolam als eerste keus benzodiazepine voor gebruik in het ziekenhuis (intraveneus, intramusculair, buccaal, of nasaal) en wanneer een intraveneuze toegangsweg beschikbaar is kan ook lorazepam intraveneus gebruikt worden.

In de Nederlandse situatie wordt clonazepam geregeld gebruikt als eerste keus benzodiazepine. Clonazepam heeft als nadeel dat het bij herhaald gebruik kan resulteren in stapeling in vetweefsel, omdat het vetoplosbaar is. Helaas is vrijwel geen literatuur beschikbaar over de werkzaamheid van clonazepam, hoewel in een observationele studie wel melding wordt gemaakt van vergelijkbare effectiviteit tussen clonazepam en midazolam (Alvarez, 2015). Vanwege het ontbreken van gerandomiseerde studies wordt dit middel vooralsnog niet als eerste keus benzodiazepine beschouwd.

In de situatie buiten het ziekenhuis kan gekozen worden voor midazolam neusspray of diazepam rectiole. Vanwege het mogelijke sociale ongemak door de toedieningswijze van diazepam rectiole lijkt midazolam neusspray wenselijker als keuzemiddel buiten het ziekenhuis. Maar vergelijkend onderzoek tussen deze twee toedieningsvormen ontbreekt en midazolam is slechts beperkt houdbaar.

Tweedelijns behandeling

De tweedelijns behandeling van een status epilepticus bestaat uit de toediening van een oplaaddosis van een anti-epilepticum. De werkzaamheid van de anti-epileptica fenytoïne, levetiracetam en valproaat werd onderzocht in een gerandomiseerde studie (Kapur, 2019). Er bleek geen verschil in effectiviteit in deze studie tussen de drie middelen. Er is derhalve geen voorkeur voor één van de drie middelen. Verdere onderbouwing hiervoor komt uit een meta-analyse met data uit enkele kleinere gerandomiseerde studies, waar eveneens geen verschil in effectiviteit werd gevonden tussen de drie middelen (Chu, 2020). De keuze voor één van de drie middelen kan deels bepaald worden door bepaalde (relatieve) contra-indicaties; valproaat wordt ontraden als onderhoudsbehandeling bij vrouwen in de vruchtbare leeftijd en ook bij patiënten met een (mogelijke) mitochondriële ziekte (EMA, 2018; Finsterer, 2010). Fenytoïne wordt ontraden bij bekende cardiale geleidingsstoornissen, zoals een sinusbradycardie, sinoatriaal blok, of tweede- en derdegraads AV-blok (Guldiken, 2016), hoewel in de gerandomiseerde studie van Kapur (2019) niet meer bijwerkingen werden gevonden in de groep patiënten die met fenytoïne werden behandeld (Kapur, 2019). Desondanks wordt geadviseerd om fenytoïne alleen te geven onder hartritmebewaking (Guldiken, 2016). Wanneer de convulsieve status epilepticus effectief is onderdrukt en men alleen snel wil opladen met een anti-epilepticum is fenytoïne geen voor de hand liggende keuze, omdat het geen eerste keus onderhouds-anti-epilepticum is.

Vooralsnog ontbreekt bewijs voor de effectiviteit van niet-medicamenteuze behandelingen van status epilepticus. In 2016 werd in een gerandomiseerde studie aangetoond dat geïnduceerde hypothermie gedurende 24 uur bij patiënten met status epilepticus niet geassocieerd was met een betere uitkomst na 90 dagen (Legriel, 2016).

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Er zijn geen grote kostenverschillen in de verschillende typen benzodiazepines en anti-epileptica. Er zijn derhalve geen grote verschillen in directe kosten te verwachten. Momenteel zijn de meeste middelen niet gepatenteerd, waardoor de kosten van de middelen relatief laag zijn en geen groot aandeel vormen in de totale kosten van de behandeling. Er zijn geen economische evaluaties bekend met betrekking tot deze uitgangsvraag.

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

De werkgroep is niet bekend met grote barrières in de praktijk op het gebied van aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie. Qua effectiviteit worden er geen grote verschillen tussen de beschikbare middelen gedetecteerd, dus naar verwachting zal voorkeur van de behandelende zorginstelling danwel het gebruikersgemak voor patiënten een rol spelen in de keuze voor middelen. Bij het toedienen van fenytoïne is het belangrijk dat mogelijkheden voor hartritmebewaking en adequate monitoring van vitale functies beschikbaar zijn, maar die zijn veelal standaard aanwezig in zorginstellingen. Vanwege frequente leveringsproblemen van de intraveneuze vorm van lorazepam in de afgelopen jaren is dit middel beperkt beschikbaar, maar met adequate beschikbaarheid van midazolam komt hiermee de zorg niet in het geding.

Figuur 1 Stroomschema: Behandeling status epilepticus bij volwassen in de ziekenhuissetting

Zie bijlage

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) task force on classification of status epilepticus defined ‘Convulsive Status Epilepticus’ (CSE) as a condition resulting either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms, which lead to abnormally and prolonged seizures (after time point t1; 5 minutes). CSE is a condition, which can have long-term consequences (after time point t2; 30 minutes), including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of seizures (Trinka, 2015). Initial treatment of a convulsive status epilepticus consists of first-line therapy with benzodiazepines, followed by second-line therapy with anti-epileptic drugs. Whereas evidence for first-line therapy with benzodiazepines is rather strong, large, randomized trials studying the effect of anti-epileptic drugs were lacking until 2019.

This module evaluates which initial treatment is most effective and beneficial for generalized convulsive status epilepticus in adults. This module contains an update of the module ‘Status Epilepticus bij volwassenen: initiële behandeling’ dated from June 2020 (including a search strategy dated from 1 January 2019).

Conclusies

1. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous phenytoin

1.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on seizure cessation when compared with phenytoin in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020 |

1.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 1.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important), 1.5. Hypotension (important), 1.6. Length of stay (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measures ‘termination of status epilepticus after drug administration’, and ‘requirement of ventilatory support’, ‘hypotension’, ‘length of stay’ were not graded.

Sources: - |

1.3. Mortality (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on mortality when compared with phenytoin in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020 |

2. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous valproate

2.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on seizure cessation when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020; Kapur, 2019 |

2.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on termination of SE after drug administration when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020; Kapur, 2019 |

2.3. Mortality (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on mortality when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020; Kapur, 2019 |

2.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on the requirement for ventilatory support when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

2.5. Hypotension (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on hypotension when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

2.6. Length of stay (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam on length of stay when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

3. Intravenous fosphenytoin versus intravenous valproate

3.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin on seizure cessation when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

3.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin on termination of SE after drug administration when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

3.3. Mortality (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin on mortality when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

3.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin on the requirement for ventilatory support when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

3.5. Hypotension (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin on hypotension when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

3.6. Length of stay (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of fosphenytoin on length of stay when compared with valproate in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kapur, 2019 |

4. Intravenous lorazepam versus intravenous diazepam

4.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on seizure cessation when compared with diazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kobata, 2020 |

4.3. Mortality (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on mortality when compared with diazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kobata, 2020 |

4.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on the requirement for ventilatory support when compared with diazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kobata, 2020 |

4.5. Hypotension (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on hypotension when compared with diazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Kobata, 2020 |

4.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical) and 4.6 Length of stay (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measures ‘termination of se after drug administration’ and ‘length of stay’ were not graded.

Sources: - |

5. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous lorazepam

5.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on seizure cessation when compared with levetiracetam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Chu, 2020 |

5.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 5.3 Mortality (important), and 5.6 Length of stay (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measures ‘termination of se after drug administration’, ‘mortality’, and ‘length of stay’ were not graded.

Sources: - |

5.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on the requirement for ventilatory support when compared with levetiracetam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Chu, 2020 |

5.5. Hypotension (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam on hypotension when compared with levetiracetam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Chu, 2020 |

6. Intravenous lorazepam + intravenous valproate versus intravenous lorazepam + intravenous levetiracetam

6.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam + valproate on seizure cessation when compared with lorazepam + levetiracetam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Nene, 2019 |

6.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 6.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important), 6.5. Hypotension (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measures ‘termination of se after drug administration’, ‘requirement of ventilatory support’, and ‘hypotension’ were not graded.

Sources: - |

6.3. Mortality (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam + valproate on mortality when compared with lorazepam + levetiracetam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Nene, 2019 |

6.6. Length of stay (important)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of lorazepam + valproate on length of stay when compared with lorazepam + levetiracetam in adults with status epilepticus.

Source: Nene, 2019 |

7. Intravenous levetiracetam + clonazepam versus intravenous placebo + clonazepam

7.1. Seizure cessation (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam + clonazepam on seizure cessation after drug administration when compared with placebo + clonazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020 |

7.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 7.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important), and 7.5. Hypotension (important)

| - GRADE | The outcome measures ‘termination of se after drug administration’, ‘requirement of ventilatory support’, and ‘hypotension’ were not graded.

Sources: - |

7.3. Mortality (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam + clonazepam on mortality when compared with placebo + clonazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020 |

7.6. Length of stay (critical)

| VERY LOW GRADE | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of levetiracetam + clonazepam on length of stay when compared with placebo + clonazepam in adults with status epilepticus.

Sources: Chu, 2020 |

The conclusions below remain maintained (2020), as no new literature was found for the following comparisons:

intravenous diazepam vs. intravenous valproate

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn beperkte aanwijzingen dat valproaat i.v. en diazepam i.v. een vergelijkbaar effect hebben op terminatie van een status epilepticus en op het opnieuw optreden van aanvallen. Het risico op hypotensie lijkt iets lager bij gebruik van valproaat.

Source: Chen, 2011 (from Prasad, 2014). |

intravenous diazepam + intravenous phenytoin vs. intravenous phenobarbital

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn beperkte aanwijzingen dat behandeling met diazepam i.v. in combinatie met fenytoïne i.v. een vergelijkbaar effect heeft op terminatie van een status epilepticus als behandeling met fenobarbital i.v. Het effect op bijwerkingen, nodig hebben van ademhalingsondersteuning en overlijden lijkt voor beide behandelingen eveneens gelijk.

Source: Shaner, 1988; Treiman, 1998 (from Prasad, 2014). |

intravenous lorazepam vs. intravenous phenytoin

| MODERATE GRADE | Het lijkt waarschijnlijk dat lorazepam i.v. bij een groter aantal patiënten leidt tot terminatie van een status epilepticus in vergelijking met fenytoïne i.v.

Source: Treiman, 1998 (from Prasad, 2014). |

intravenous lorazepam vs. intramuscular midazolam

| MODERATE GRADE | Het lijkt waarschijnlijk dat midazolam i.m. bij een groter aantal patiënten met een status epilepticus buiten het ziekenhuis tot terminatie van de aanval leidt vergeleken met lorazepam i.v. Dit lijkt eveneens te gelden voor het risico op ICU opname of opname elders in het ziekenhuis. Beide middelen lijken een vergelijkbaar risico te geven op het opnieuw optreden van aanvallen, op bijwerkingen en op de noodzaak tot endotracheale intubatie.

Source: Silbergleit, 2012 (from Prasad, 2014). |

intravenous valproate vs. intravenous phenytoin

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn beperkte aanwijzingen dat valproaat i.v. en diazepam i.v. een vergelijkbaar effect hebben op terminatie van een status epilepticus

Source: Brigo, 2016a (using Agarwal; 2007; Chakravarthi et al. 2015; Gilad; 2008; Mundlamuri, 2015) |

intravenous valproate vs. intravenous phenobarbital

| LOW GRADE | Er zijn aanwijzingen dat fenobarbital i.v effectiever is in het beëindigen van een convulsieve status epilepticus dan valproaat i.v. Hierbij moet rekening worden gehouden met een groter risico op ernstige bijwerkingen bij gebruik van fenobarbital i.v.

Source: Su, 2016 |

intravenous valproate vs. intravenous phenytoin

| VERY LOW GRADE | Er zijn beperkte aanwijzingen dat valproaat i.v. en fenytoïne i.v. een vergelijkbaar effect hebben op het beëindigen van een convulsieve status epilepticus. Hierbij moet rekening worden gehouden met een groter risico op cardiovasculaire bijwerkingen bij gebruik van fenytoïne.

Source: Amiri-Nikpour, 2018 |

Samenvatting literatuur

Description of studies

Chu (2020) performed a systematic review and meta-analyses to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravenous levetiracetam in patients with status epilepticus. Only RCTs, comparing intravenous levetiracetam to other antiepileptic drugs were included in this systematic review. Six RCTs with a total of 543 patients were included. The definition of ‘convulsive status epilepticus’ varied slightly from study to study. All studies included generalized convulsive status epilepticus participants, whereas three studies (Gujjar, 2017; Misra, 2012; Chakravarthi, 2015) included several patients presenting with focal or subtle convulsive status epilepticus. Four comparisons were available:

- intravenous levetiracetam vs. intravenous phenytoin (Gujjar, 2017; Chakravarthi, 2015);

- intravenous levetiracetam vs. intravenous valproate (Tripathi, 2009);

- intravenous levetiracetam vs. intravenous lorazepam (Misra, 2012); and

- intravenous levetiracetam plus clonazepam vs. intravenous placebo plus clonazepam (Mundlamuria, 2015).

The dose, maintenance dose, and injection timing of levetiracetam and control drugs varied between studies. Mundlamuri (2015) followed their participants for one month after discharge from hospital), and in other studies patients were followed only during their hospital stay. Regarding risk of bias, in five RCTs was selection bias detected and in five RCTs was selective reporting bias detected, but all studies mentioned adequate blinding.

Relevant outcome measures included drug administration to seizure cessation (critical), termination of status epilepticus after drug administration (critical), mortality (important), and requirement for ventilatory support (important).

Kobata (2020) performed a systematic review to compare intravenous diazepam and intravenous lorazepam for the emergency treatment of adult status epilepticus. Two RCTs (Leppik, 1983; Alldredge, 2001) with a total of 204 adult status epilepticus patients at an emergency setting were included. Leppik (1983) compared intravenous diazepam (10 mg) to intravenous lorazepam (4 mg) and Alldredge (2001) compared intravenous diazepam (5 mg) to intravenous lorazepam (2 mg). For both RCTs, when the seizures did not terminate or recurred, second injections of identical doses of the same benzodiazepines were given. The study populations differed: Leppik (1983) included convulsive and non-convulsive SE, whereas Alldredge (2001) included only generalized tonic-clonic seizure. Risk of bias was assessed as ‘high’ for Leppik (1983) and assessed as ‘low’ for Alldredge (2001). Relevant outcome measures include seizure cessation (critical), mortality (important), hypotension (important), respiratory depression (important).

Kapur (2019) performed an RCT to compare the efficacy and safety of intravenous levetiracetam, intravenous fosphenytoin, and intravenous valproate in children and adults with convulsive status epilepticus that were unresponsive to treatment with benzodiazepines. Patients (n=384) were randomized into the intravenous levetiracetam group (n=145, mean age ± SD: 33.3 ± 26.0, 53% male), intravenous fosphenytoin group (n=118, mean age ± SD: 32.8 ± 25.4, 60% male), or intravenous VPA group (n=121, mean age ± SD: 32.2 ± 25.4, 54% male). A total of 39% of the patients who were enrolled were children and adolescents (up to 17 years of age), 48% were adults (18 to 65 years of age), and 13% were older adults (>65 years of age). To answer our clinical question, we extracted the results from the adult subgroup analysis intention to treat analyses were performed. Relevant outcome measures include seizure cessation (critical), mortality (important), hypotension (important), respiratory depression (important).

Nene (2019) conducted an RCT to compare the efficacy of valproate and levetiracetam following initial intravenous lorazepam in elderly patients (>60 years) with generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Intravenous lorazepam was followed by administration of intravenous valproate or levetiracetam based on the treatment arm to which the patient was randomized. All patients received initial intravenous lorazepam (0.1 mg/kg) followed by one of the two antiepileptic drugs: parenteral valproate (20-25 mg/kg) or intravenous levetiracetam (20-25 mg/kg). A total of 118 patients who had generalized convulsive status epilepticus were randomized (valproate: n=60, mean age: 66.6 ± 6.7, 31% female; levetiracetam: n=58, mean age: 68.5 ± 8.0, 41% female). A total of 100 patients (valproate: n=50, mean age: 66.6 ± 6.7, 11% female; levetiracetam n=50) completed the study. Intention to treat analyses were performed. Relevant outcome measures include seizure cessation (critical), mortality (important), hypotension (important), respiratory depression (important).

This module is an update from the module dd. June 2020 (including a search until 1 January 2019). No new literature was found regarding the following comparisons:

- intravenous diazepam + intravenous phenytoin vs. intravenous phenobarbital

- intravenous diazepam + intravenous phenytoin vs. intravenous phenytoin

- intravenous diazepam vs. intravenous valproate

- intravenous lorazepam vs. intramuscular midazolam

- intravenous lorazepam vs. intravenous phenobarbital

- intravenous valproate vs. intravenous phenobarbital

- intravenous valproate vs. intravenous phenytoin

Thus, the previous conclusions remain valid. The description of previous included studies is presented as Appendix 1 (2020).

Results

1. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous phenytoin

1.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

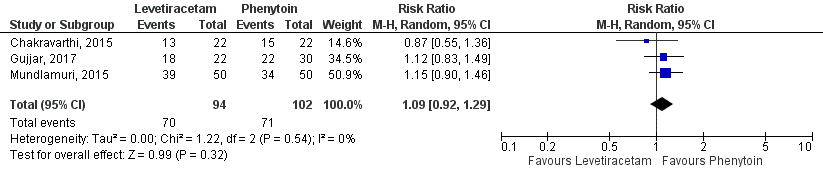

For the comparison between levetiracetam and phenytoin, three studies (Chakravarthi, 2015; Mundlamuri, 2015; Gujjar, 2017) with 196 participants were combined by Chu (2020) in a meta-analysis. Analyses showed that seizure cessation was present in 70 out of 94 (74%) patients in the levetiracetam-group and in 71 out of 102 (70%) phenytoin-group patients, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.09 (95%CI 0.92 to 1.29), see Figure 1. The difference between the groups was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

1.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Not reported for the comparison between levetiracetam and phenytoin.

1.3 Mortality (important)

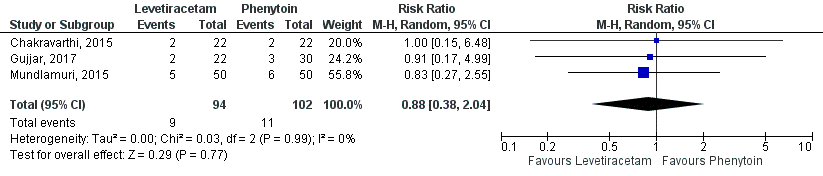

Chu (2020) defined ‘mortality’ as in hospital mortality. Analyses showed that hospital mortality was present in 9 out of 94 patients (10%) patients in the levetiracetam-group and in 11 out of 102 patients (11%) phenytoin-group patients, ressulting in a risk ratio of 0.88 (95%CI 0.38 to 2.04), see Figure 2. This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant.

The outcomes 1.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important), 1.5 Hypotension (important), and 1.6 Length of stay (important) were not reported for the comparison between levetiracetam and phenytoin.

Figure 1 Studies comparing intravenous levetiracetam and intravenous phenytoin: seizure cessation.

Figure 2 Studies comparing intravenous levetiracetam and intravenous phenytoin: hospital mortality.

2. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous valproate

2.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

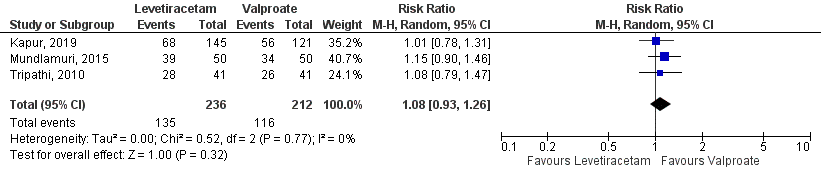

For the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, two studies (Tripathi, 2010; Mundlamuri, 2015) with 182 participants were combined in a meta-analysis (Chu, 2020). One additional RCT (Kapur, 2019) including 266 patients was added to this comparison. Kapur (2020) assessed cessation of seizures within 60 minutes.

Seizure cessation was present in 135 out of 236 (57%) patients in the levetiracetam-group and in 116 out of 212 (55%) patients in the valproate-group, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.08 (95%CI 0.93 to 1.26), see Figure 3. The difference between the groups was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

2.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

For the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, one RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed the time to termination of seizures. This outcome was defined as the interval from the start of infusion of the trial drug to the cessation of clinically apparent seizures.

Data were available for 24 patients (n=14 levetiracetam, n=10 valproate). Median time from start of trial-drug infusion to termination of seizures for patients with treatment success was 10.5 minutes (interquartile range: 5.7 to 15.5) in the levetiracetam-group and 7.0 minutes (interquartile range: 4.6 to 14.9) in the valproate-group. If the median is interpreted as a mean value, then there could potentially be a clinically relevant difference. However, since this is a median (data is skewed), no statement can be made about the clinically relevant difference.

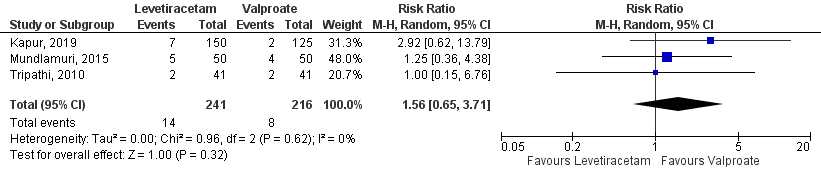

2.3 Mortality (important)

Chu (2020) defined ‘mortality’ as in hospital mortality, including two studies (Tripathi, 2010; Mundlamuri, 2015). One additional RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed mortality at hospital discharge or 30 days, whichever came first.

Mortality was present in 14 out of 241 (5.8%) patients in the levetiracetam-group and in 8 out of 216 (3.7%) patients in the valproate-group, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.56 (95%CI 0.65 to 3.71), see Figure 4. The difference between the groups was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Herewith, the very low number of events and the wide confidence interval should be considered.

2.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important).

Kapur (2019) assessed acute respiratory depression at hospital discharge or 30 days, whichever came first. In the levetiracetam-group in 12 out of 150 patients (8%) and in the valproate-group 10 out of 125 patients (8%) experienced acute respiratory depression. This resulted in a risk ratio is 1.00 (95%CI 0.45 to 2.24). This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant. The very low number of events and the wide confidence interval should be considered.

2.5 Hypotension (important)

For the comparison between levetiracetam versus valproate, Kapur (2019) assessed life-threatening hypotension within 60 min after start of trial drug infusion. In the levetiracetam-group in 1 out of 150 patients (1%) and in the valproate-group 2 out of 125 patients (2%) experienced hypotension.

2.6 Length of stay (important)

For the comparison between levetiracetam versus valproate, one RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed the length of stay. Length of stay was defined as admission to the ICU; the length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay.

In the levetiracetam-group 87 out of 145 patients (60%) and in the valproate-group 71 out of 121 patients (59%) were admitted to the ICU, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.02 (95%CI 0.84 to 1.25). Median length of ICU stay was 1 day (interquartile range: 0 to 3) for both groups.

Median length of total hospital stay was 3 days (interquartile range: 1 to 7) in the levetiracetam-group and 3 days (interquartile range: 2 to 6) in the valproate-group. These differences were not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

Figure 3 Studies comparing intravenous levetiracetam and intravenous valproate:

seizure cessation.

Figure 4 Studies comparing intravenous levetiracetam and intravenous valproate:

hospital mortality.

3. Intravenous fosphenytoin versus intravenous valproate

3.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

For the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, one RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed cessation of seizures within 60 minutes. Seizure cessation was found in 53 of 118 (45%) in the fosphenytoin-group and 56 of 121 (46%) in the valproate-group. This resulted in a risk ratio of 0.97 (95%CI 0.74 to 1.28). This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

3.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

For the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, one RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed the time to termination of seizures. This outcome was defined as the interval from the start of infusion of the trial drug to the cessation of clinically apparent seizures.

Data were available for 25 patients (n=15 fosphenytoin, n= 10 valproate). Median time from start of trial-drug infusion to termination of seizures for patients with treatment success was 11.7 minutes (interquartile range: 7.5 to 20.9) in the fosphenytoin-group and 7.0 minutes (interquartile range: 4.6 to 14.9) in the valproate-group. No statement can be made about the clinically relevant difference as these are median values (data is skewed).

3.3 Mortality (important)

For the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, one RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed mortality at hospital discharge or 30 days, whichever came first. In the fosphenytoin-group 3 out of 125 patients (2%) died and in the valproate-group 2 out of 125 patients (2%) died. When valproateis compared to fosphenytoin, the risk ratio is 1.50 (95%CI 0.26 to 8.82). Herewith, the very low number of events (5 in total) and the wide confidence interval should be considered.

3.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important).

Kapur (2019) assessed acute respiratory depression at hospital discharge or 30 days, whichever came first. In the fosphenytoin-group 16 out of 125 patients (13%) and in the valproate-group 10 out of 125 patients (8%) experienced acute respiratory depression. When fosphenytoin compared to valproate, the risk ratio is 1.60 (95%CI 0.76 to 3.39). This difference was statistically significant but clinically relevant. Caution is needed due to the wide confidence interval.

3.5 Hypotension (important)

For the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, Kapur (2019) assessed life-threatening hypotension within 60 min after start of trial drug infusion. In the fosphenytoin-group 4 out of 125 patients (3%), and in the valproate-group 2 out of 125 patients (2%) experienced hypotension.

3.6 Length of stay (important)

For the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, one RCT (Kapur, 2019) assessed the length of stay. Length of stay was defined as admission to the ICU; the length of ICU stay, and length of hospital stay.

In the fosphenytoin-group 70 out of 118 patients (59%) and in the valproate-group 71 out of 121 patients (59%) were admitted to the ICU, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.75 (95%CI 1.31 to 2.34). This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant.

Median length of ICU stay was 1 day (interquartile range: 0 to 3) in both groups. Median length of total hospital stay was 3 days (interquartile range: 1 to 6) in the fosphenytoin-group and 3 days (interquartile range: 2 to 6) in the valproate-group. These differences were not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

4. Intravenous lorazepam versus intravenous diazepam

4.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

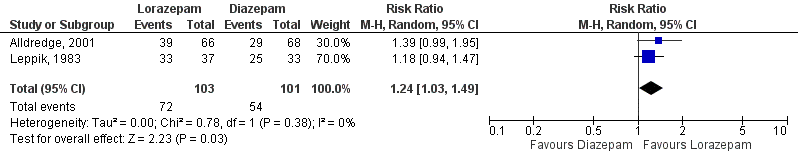

For the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, two studies (Leppik, 1983; Alldredge, 2001) with 204 participants were combined in a meta-analysis (Kobata, 2020).

Seizure cessation was present in 54 out of 101 patients (53%) patients in the diazepam-group and in 72 out of 103 patients (70%) lorazepam-group patients, resulting in a risk ratio of

4.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Not reported for the comparison diazepam versus lorazepam.

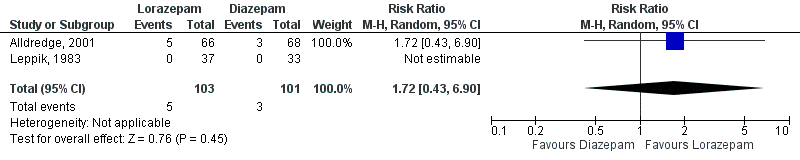

4.3 Mortality (important)

For the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, two studies (Leppik, 1983; Alldredge, 2001) with 204 participants were combined in meta-analysis (Kobata, 2020). Kobata (2020) defined ‘mortality’ as mortality at discharge. Mortality at discharge was present in 3 out of 101 patients (3%) in the diazepam-group and in 5 out of 103 patients (5%) lorazepam-group patients, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.72 (95%CI 0.43 to 6.90), see Figure 6. This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Caution is needed due to the very low number of events and the wide confidence interval.

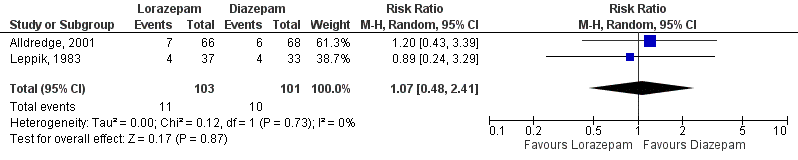

4.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Kobata (2020) compared diazepam to lorazepam and assessed ventilatory support based on two studies (Leppik, 1983; Alldredge, 2001), representing 204 patients. Analyses showed that ventilatory support was needed in 10 out of 101 patients (10%) in the diazepam-group and in 11 out of 103 patients (11%) lorazepam-group patients, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.07 (95%CI 0.48 to 2.41), see Figure 7. This difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

4.5 Hypotension (important)

One study (Leppik, 1983) included in Kobata (2020) assessed ‘hypotension’. Leppik (1983) assessed hypotension in 70 patients. In the levetiracetam-group and diazepam-group, hypotension occurred in 1 out of 37 patients (2.7%) and 0 out of 33 patients (0%), respectively.

4.6 Length of stay (important)

Not reported for the comparison diazepam versus lorazepam.

Figure 5 Studies comparing intravenous Lorazepam and intravenous Diazepam:

seizure cessation.

Figure 6 Studies comparing intravenous Lorazepam and intravenous Diazepam:

mortality.

Figure 7 Studies comparing intravenous Lorazepam and intravenous Diazepam:

requirement of ventilatory support.

5. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous lorazepam

5.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

For the comparison between levetiracetam and lorazepam, one study (Misra, 2012) was selected from the meta-analysis (Chu, 2020). Misra (2012) included 79 patients and defined termination after drug administration at 10 minutes. Seizure cessation was present in 29 out of 38 patients (76%) in the levetiracetam-group and in 31 out of 41 patients (76%) in the lorazepam-group patients, resulting in a risk ratio of 1.01 (95%CI 0.79 to 1.29). This difference between the groups was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

5.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Not reported for the comparison levetiracetam versus lorazepam.

5.3 Mortality (important)

Not reported for the comparison levetiracetam versus lorazepam.

5.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Analyses showed that in the levetiracetam-group 4 out of 38 patients (11%) and in the lorazepam-group 10 out of 41 patients (24%) used ventilatory support, resulting in a risk ratio of 0.43 (95%CI 0.15 to 1.26). This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Caution is needed due to the very low number of events.

5.5 Hypotension (important)

Analyses showed that in the levetiracetam-group 2 out of 38 patients (5%) and in the lorazepam-group 8 out of 41 patients (20%) had hypotension, resulting in a risk ratio of 0.27 (95%CI 0.06 to 1.19). This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Caution is needed due to the very low number of events.

5.6 Length of stay (important)

Not reported for the comparison levetiracetam versus lorazepam.

6. Intravenous lorazepam + intravenous valproate versus intravenous lorazepam + intravenous levetiracetam

6.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

For the comparison between valproate and levetiracetam following initial intravenous lorazepam, one RCT (Nene, 2019) assessed termination of SE as no recurrence of seizures after half an hour of infusion of study drugs. Intention to treat analysis (n=118) showed that valproate following lorazepam led to seizure control in 41 out of 60 patients (68%), while levetiracetam following lorazepam led to seizure control in 43 out of 58 patients (74%).

This resulted in a risk ratio of 0.92 (95%CI 0.73 to 1.16), this difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

6.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Not reported for the comparison lorazepam + valproate versus lorazepam + levetiracetam.

6.3 Mortality (important)

Nene (2019) assessed 1-month mortality comparing valproate and levetiracetam. The 30-day mortality was comparable in both groups (valproate: n=13, 22.4%; levetiracetam: n=10, 18.2%). this difference resulted in a risk ratio of 1.26 (95%CI 0.60 to 2.64). This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Herewith, the very low number of events and the wide confidence interval should be considered.

6.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Not reported for the comparison lorazepam + valproate versus lorazepam + levetiracetam.

6.5 Hypotension (important)

Not reported for the comparison lorazepam + valproate versus lorazepam + levetiracetam.

6.6 Length of stay (important)

Nene (2019) assessed the length of hospital stay comparing valproate and levetiracetam. Mean length of hospital stay was 3.6 days (SD: 1.9) in the valproate-group and 4.4 days (SD: 3.9) in the levetiracetam-group.

7. Intravenous levetiracetam + clonazepam versus intravenous placebo + clonazepam

7.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

For the comparison between adding levetiracetam to clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam, one study (Navarro, 2016) was selected from the meta-analysis (Chu, 2020). Navarro (2016) included 136 patients and defined termination of SE after drug administration within 15 minutes. Status epilepticus was controlled by levetiracetam in 57 out of 68 patients (84%) and by placebo in 50 out of 68 patients (74%), which resulted in a risk ratio of 1.14 (95%CI 0.96 to 1.36). This difference was not statistically significant, but clinically relevant.

7.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Not reported for the comparison levetiracetam and clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam.

7.3 Mortality (important)

Navarro (2016) assessed mortality at 15 days after admission to hospital or earlier if discharged from hospital. Mortality was comparable in both groups (clonazepam plus levetiracetam: n=3, 5%; clonazepam plus placebo: n=4, 6%). This difference resulted in a risk ratio of 0.74 95%CI 0.17 to 3.17). This difference was not statistically significant but clinically relevant. Herewith, the very low number of events and the wide confidence interval should be considered.

7.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Not reported for the comparison levetiracetam and clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam.

7.5 Hypotension (important)

Not reported for the comparison levetiracetam and clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam.

7.6 Length of stay (important)

Navarro (2016) assessed the length of hospital stay comparing levetiracetam and clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam. Median length of hospital stay was 10 days (range 1 to 15) in the levetiracetam-group and 10 days (range 1 to 15) in the placebo-group.

Median length of ICU stay was 3 days (range 0 to 15) in the levetiracetam-group and 3 days (range 1 to 15) in the placebo-group.

Level of evidence of the literature

1. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous phenytoin

1.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison levetiracetam and phenytoin, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias), imprecision (-1; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference), and conflicting results between studies (-1; heterogeneity).

1.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the comparison intramuscular levetiracetam and phenytoin, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference and relatively small number of patients).

The outcomes 1.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 1.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important), 1.5 Hypotension (important), and 1.6 Length of stay (important) were not reported and could not be graded.

2. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous valproate

2.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; because of crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

2.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; because of a small number of patients from only one study).

2.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, only one study, large confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

2.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important).

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘ventilatory support’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, only one study, large confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

2.5 Hypotension (important).

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypotension’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, a small number of patients from only one study).

2.6 Length of stay (important).

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘length of stay’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference, a small number of patients from only one study).

3. Intravenous fosphenytoin versus intravenous valproate

3.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; because of crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

3.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical)

Regarding the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘termination of SE after drug administration’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; because of a small number of patients from only one study).

3.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, only one study, large confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

3.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Regarding the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘ventilatory support’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, only one study, large confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

3.5 Hypotension (important)

Regarding the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypotension’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, a small number of patients from only one study).

3.6 Length of stay (important)

Regarding the comparison between fosphenytoin and valproate, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘length of stay’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference, a small number of patients from only one study).

4. Intravenous lorazepam versus intravenous diazepam

4.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population).

4.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, large confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

4.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Regarding the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘ventilatory support’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, large confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

4.5 Hypotension (important)

Regarding the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypotension’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; very low number of events, relatively small study population).

The outcomes 4.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical) and 4.6 Length of stay (important) were not reported and could not be graded.

5. Intravenous levetiracetam versus intravenous lorazepam

5.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison between levetiracetam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population, confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

5.4 Requirement of ventilatory support (important)

Regarding the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘ventilatory support’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population, confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

5.5 Hypotension (important)

Regarding the comparison between diazepam and lorazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘hypotension’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population, low number of events, confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

The outcomes 5.2 Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 5.3 Mortality (important), and 5.6 Length of stay (important) were not reported and could not be graded.

6. Intravenous lorazepam + intravenous valproate versus intravenous lorazepam + intravenous levetiracetam

6.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison between valproate and levetiracetam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population from only one study, confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

6.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the comparison between valproate and levetiracetam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population from only one study).

6.6 Length of stay (important)

Regarding the comparison between valproate and levetiracetam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘length of stay’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population from only one study).

The outcomes 6.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical). 6.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important), 6.5. Hypotension (important) were not reported and could not be graded.

7. Intravenous levetiracetam + clonazepam versus intravenous placebo + clonazepam

7.1 Seizure cessation (critical)

Regarding the comparison between adding levetiracetam to clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘seizure cessation’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population from only one study, confidence interval crosses boundaries of clinical important difference).

7.3 Mortality (important)

Regarding the comparison between adding levetiracetam to clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘mortality’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population from only s study, very low number of events).

7.6 Length of stay (important)

Regarding the comparison between adding levetiracetam to clonazepam vs. adding placebo to clonazepam, the level of evidence regarding the outcome measure ‘length of stay’ started as high and was downgraded by 3 levels to very low because of study limitations (-1; risk of bias) and imprecision (-2; relatively small study population from only one study).

The outcomes 7.2. Termination of SE after drug administration (critical), 7.4. Requirement of ventilatory support (important), and 7.5. Hypotension (important) were not reported and could not be graded.

Zoeken en selecteren

A systematic review of the literature was performed to answer the following question:

Which type, dosage and form of medication is most effective in the treatment of status epilepticus in adults with generalized convulsive status epilepticus?

P: adults with status epilepticus

I: anti-epileptic medication (such as diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, brivaracetam, lacosamide, levetiracetam, phenytoin, valproate and other, new anti-epileptic medication)

C: same medication but other dosage and/or form, other type of medication, no treatment/placebo

O: (time from) drug administration to seizure cessation; (duration of) persistent seizure cessation (dichotomous and continuous); requirement for ventilatory support, hypotension, patient satisfaction, mortality, length of hospital stay

Relevant outcome measures

The working group defined convulsive status epilepticus as stated in the ILAE classification of 2015: “Status epilepticus is a condition resulting either from the failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the initiation of mechanisms, which lead to abnormally, prolonged seizures (after time point t1). It is a condition, which can have long-term consequences (after time point t2), including neuronal death, neuronal injury, and alteration of neuronal networks, depending on the type and duration of seizures.” (Trinka, 2015). For convulsive status epilepticus time point t1 is 5 minutes and time point t2 is 30 minutes.

The working group considered (time from drug administration to) seizure cessation and (duration of) continued seizure cessation as a critical outcome measure for decision making; mortality, requirement for ventilatory support, hypotension, length of hospital stay, and patient satisfaction as an important outcome measure for decision making.

A priori, the working group did not define the outcome measures listed above but used the definitions used in the studies. Patient satisfaction had to be assessed using validated instruments. Length of hospital stay is defined as the overall length of time a patient is hospitalized.

Per outcome, the working group defined the following differences as a minimal clinically (patient) important differences:

Dichotomous outcomes (relative risk; yes/no):

- From drug administration to seizure cessation within a certain time period: ≥10%

- Persistent seizure cessation at least one hour: ≥10%

- Respiratory depression (requirement for ventilatory support): ≥10%

- Mortality: ≥10%

Continuous outcomes:

- Time from drug administration to seizure cessation: ≥2 minutes

- Duration of persistent seizure cessation: ≥30 minutes

- Hypotension: ≥10%

- Patient satisfaction: ≥10% difference on a validated scale

- Length of hospital stay: ≥2 days

Search and select (Methods)

The search strategy, which dated from 01-01-2019 was updated. The databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms from 01-01-2019 (last search) until 21-06-2021. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. One search was conducted for all modules concerning the treatment of status epilepticus. The search was limited to systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials. The systematic literature search resulted in 305 hits. Studies for this module were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic review (searched in at least two databases, and detailed search strategy, risk of bias assessment and results of individual studies available) or randomized controlled trial;

- full-text English language publication;

- adults aged ≥ 18 years;

- studies including ≥ 20 (ten in each study arm) patients; and

- studies according to the PICO.

After reading the full text five studies were included in the literature summary of this module.

Results

Five studies were included in the analysis of the literature, of which two systematic reviews and three randomized controlled trials. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Agarwal P, Kumar N, Chandra R, Gupta G, Antony AR, Garg N. Randomized study of intravenous valproate and phenytoin in status epilepticus. Seizure. 2007 Sep;16(6):527-32. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.04.012. Epub 2007 Jul 9. PMID: 17616473.

- Alldredge BK, Gelb AM, Isaacs SM, Corry MD, Allen F, Ulrich S, Gottwald MD, O'Neil N, Neuhaus JM, Segal MR, Lowenstein DH. A comparison of lorazepam, diazepam, and placebo for the treatment of out-of-hospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2001 Aug 30;345(9):631-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002141. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2001 Dec 20;345(25):1860. PMID: 11547716.

- Alvarez V, Lee JW, Drislane FW, Westover MB, Novy J, Dworetzky BA, Rossetti AO. Practice variability and efficacy of clonazepam, lorazepam, and midazolam in status epilepticus: a multicenter comparison. Epilepsia. 2015 Aug;56(8):1275-85. doi: 10.1111/epi.13056. PMID: 26140660

- Amiri-Nikpour MR, Nazarbaghi S, Eftekhari P, Mohammadi S, Dindarian S, Bagheri M, Mohammadi H. Sodium valproate compared to phenytoin in treatment of status epilepticus. Brain Behav. 2018 Mar 23;8(5):e00951. doi: 10.1002/brb3.951. PMID: 29761006; PMCID: PMC5943732.

- Brigo F, Bragazzi N, Nardone R, Trinka E. Direct and indirect comparison meta-analysis of levetiracetam versus phenytoin or valproate for convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2016 Nov;64(Pt A):110-115. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.09.030. Epub 2016 Oct 11. PMID: 27736657.

- Chakravarthi S, Goyal MK, Modi M, Bhalla A, Singh P. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin in management of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurosci. 2015 Jun;22(6):959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.12.013. Epub 2015 Apr 18. PMID: 25899652.

- Chen WB, Gao R, Su YY, Zhao JW, Zhang YZ, Wang L, Ren Y, Fan CQ. Valproate versus diazepam for generalized convulsive status epilepticus: a pilot study. Eur J Neurol. 2011 Dec;18(12):1391-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03420.x. Epub 2011 May 9. PMID: 21557791.

- Chu SS, Wang HJ, Zhu LN, Xu D, Wang XP, Liu L. Therapeutic effect of intravenous levetiracetam in status epilepticus: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Seizure. 2020 Jan;74:49-55. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.11.007. Epub 2019 Nov 22. PMID: 31830677.

- EMA, 2018. European Medicines Agency 2018; 31/05/2018 EMA/375438/2018. Nieuwe maatregelen ter vermijding van blootstelling aan valproaat bij zwangerschap onderschreven. Link: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/valproate-article-31-referral-new-measures-avoid-valproate-exposure-pregnancy-endorsed_nl.pdf

- Finsterer, J., & Segall, L. (2010). Drugs interfering with mitochondrial disorders. Drug and chemical toxicology, 33(2), 138-151.

- Gilad R, Izkovitz N, Dabby R, Rapoport A, Sadeh M, Weller B, Lampl Y. Treatment of status epilepticus and acute repetitive seizures with i.v. valproic acid vs phenytoin. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008 Nov;118(5):296-300. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01097.x. PMID: 18798830.

- Gujjar AR, Nandhagopal R, Jacob PC, Al-Hashim A, Al-Amrani K, Ganguly SS, Al-Asmi A. Intravenous levetiracetam vs phenytoin for status epilepticus and cluster seizures: A prospective, randomized study. Seizure. 2017 Jul;49:8-12. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.05.001. Epub 2017 May 4. PMID: 28528211.

- Guldiken, B., Rémi, J., & Noachtar, S. (2016). Cardiovascular adverse effects of phenytoin. Journal of neurology, 263(5), 861-870.

- Kobata H, Hifumi T, Hoshiyama E, Yamakawa K, Nakamura K, Soh M, Kondo Y, Yokobori S; Japan Resuscitation Council (JRC) Neuroresuscitation Task Force and the Guidelines Editorial Committee. Comparison of diazepam and lorazepam for the emergency treatment of adult status epilepticus: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Acute Med Surg. 2020 Nov 4;7(1):e582. doi: 10.1002/ams2.582. PMID: 33489240; PMCID: PMC7809602.

- Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, Shinnar S, Conwit R, Meinzer C, Cock H, Fountain N, Connor JT, Silbergleit R; NETT and PECARN Investigators. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 28;381(22):2103-2113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905795. PMID: 31774955; PMCID: PMC7098487.

- Leppik IE, Derivan AT, Homan RW, Walker J, Ramsay RE, Patrick B. Double-blind study of lorazepam and diazepam in status epilepticus. JAMA. 1983 Mar 18;249(11):1452-4. PMID: 6131148.

- Misra UK, Kalita J, Maurya PK. Levetiracetam versus lorazepam in status epilepticus: a randomized, open labeled pilot study. J Neurol. 2012 Apr;259(4):645-8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6227-2. Epub 2011 Sep 6. PMID: 21898137.

- Mundlamuri RC, Sinha S, Subbakrishna DK, Prathyusha PV, Nagappa M, Bindu PS, Taly AB, Umamaheswara Rao GS, Satishchandra P. Management of generalised convulsive status epilepticus (SE): A prospective randomised controlled study of combined treatment with intravenous lorazepam with either phenytoin, sodium valproate or levetiracetam--Pilot study. Epilepsy Res. 2015 Aug;114:52-8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.04.013. Epub 2015 May 1. PMID: 26088885.

- Navarro V, Dagron C, Elie C, Lamhaut L, Demeret S, Urien S, An K, Bolgert F, Tréluyer JM, Baulac M, Carli P; SAMUKeppra investigators. Prehospital treatment with levetiracetam plus clonazepam or placebo plus clonazepam in status epilepticus (SAMUKeppra): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2016 Jan;15(1):47-55. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00296-3. Epub 2015 Nov 28. PMID: 26627366.

- Nene D, Mundlamuri RC, Satishchandra P, Prathyusha PV, Nagappa M, Bindu PS, Raghavendra K, Saini J, Bharath RD, Thennarasu K, Taly AB, Sinha S. Comparing the efficacy of sodium valproate and levetiracetam following initial lorazepam in elderly patients with generalized convulsive status epilepticus (GCSE): A prospective randomized controlled pilot study. Seizure. 2019 Feb;65:111-117. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2019.01.015. Epub 2019 Jan 15. PMID: 30682680.

- NIV, 2014. Richtlijn Diabetes Mellitus - Behandeling ernstige hypoglykemie. Beoordeeld: 20-02-2014. Link: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/diabetes_mellitus/hypoglykemie/behandeling_ernstige_hypoglykemie.html

- Prasad M, Krishnan PR, Sequeira R, Al-Roomi K. Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Sep 10;2014(9):CD003723. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003723.pub3. PMID: 25207925; PMCID: PMC7154380.

- Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch Y, Barsan W; NETT Investigators. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2012 Feb 16;366(7):591-600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107494. PMID: 22335736; PMCID: PMC3307101.

- Shaner DM, McCurdy SA, Herring MO, Gabor AJ. Treatment of status epilepticus: a prospective comparison of diazepam and phenytoin versus phenobarbital and optional phenytoin. Neurology. 1988 Feb;38(2):202-7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.2.202. PMID: 3277082.

- Shorvon, S., & Ferlisi, M. (2011). The treatment of super-refractory status epilepticus: a critical review of available therapies and a clinical treatment protocol. Brain, 134(10), 2802-2818.

- Spencer DC, Sinha SR, Choi EJ, Cleveland JM, King A, Meng TC, Pullman WE, Sequeira DJ, Van Ess PJ, Wheless JW. Safety and efficacy of midazolam nasal spray for the treatment of intermittent bouts of increased seizure activity in the epilepsy monitoring unit: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2020 Nov;61(11):2415-2425. doi: 10.1111/epi.16704. Epub 2020 Nov 2. PMID: 33140403.

- Su Y, Liu G, Tian F, Ren G, Jiang M, Chun B, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Ye H, Gao D, Chen W. Phenobarbital Versus Valproate for Generalized Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Adults: A Prospective Randomized Controlled Trial in China. CNS Drugs. 2016 Dec;30(12):1201-1207. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0388-6. PMID: 27878767.

- Treiman DM, Meyers PD, Walton NY, Collins JF, Colling C, Rowan AJ, Handforth A, Faught E, Calabrese VP, Uthman BM, Ramsay RE, Mamdani MB. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998 Sep 17;339(12):792-8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391202. PMID: 9738086.

- Tripathi M, Vibha D, Choudhary N, Prasad K, Srivastava MV, Bhatia R, Chandra SP. Management of refractory status epilepticus at a tertiary care centre in a developing country. Seizure. 2010 Mar;19(2):109-11. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2009.11.007. Epub 2010 Jan 19. PMID: 20034814.

- Trinka E, Cock H, Hesdorffer D, Rossetti AO, Scheffer IE, Shinnar S, Shorvon S, Lowenstein DH. A definition and classification of status epilepticus--Report of the ILAE Task Force on Classification of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2015 Oct;56(10):1515-23. doi: 10.1111/epi.13121. Epub 2015 Sep 4. PMID: 26336950.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Intervention (I) | Comparison / control (C)

| Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments |

Chu, 2020

PS. Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR. | SR and meta-analysis of RCTs.

Literature search up to October 2018.

A: Tripathi, 2010 B: Misra, 2012 C: Chakravarthi, 2015 D: Mundlamuri, 2015 E: Navarro, 2016 F: Gujjar, 2017

A: RCT B: RCT C: RCT D: RCT E: RCT F: RCT

Setting and Country: Various

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial / industrial co-authorship

| Inclusion criteria SR: * Randomized, blinded or not blinded, prospectively designed controlled trials. * Trials comparing IV LEV to other AEDs. * Convulsive or non-convulsive SE at any age.

Exclusion criteria SR: * Design of trial was uncontrolled, non-randomized.

6 studies included

Important baseline patient characteristics: No. of patients A: 41 vs. 41 B: 38 vs. 41 C: 22 vs 22 D: 50 vs. 50 vs. 50 E: 68 vs. 68 F: 22 vs. 30

Mean age ± SD A: 21.08 ± 9.7 vs. 26.62 ± 10.1 B: 39.16 ± 21.16 vs. 38.90 ± 23.25 C: 39.00 ± 18.40 vs. 31.82 ± 12.68 D: 34.78 ± 13.64 vs. 33.12 ± 11.99 vs. 33.24 ± 13.39 E: 55 ± 18 vs. 53 ± 18 F: 38 ± 19 vs. 37 ± 19

Sex (M/F) A: 23/18 vs. 19/22 B: 21/17 vs. 30/11 C: 12/10 vs. 15/7 D: 32/18 vs. 28/22 vs. 28/22 E: 49/19 vs. 45/23 F: 13/9 vs. 21/9

SE type A: GCSE (n=82) B: GCSE (n=73), subtle convulsive SE (n=6) C: GCSE (n=41), focal convulsive SE (n=3) D: GCSE (n=150) E: GCSE (n=136) F: GCSE (n=50), partial (n=2)

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. | A: IV LEV (30 mg/kg at the rate of 5 mg/kg/min IV)

B: IV LEV (20 mg/kg over 15 min IV)

C: IV LEV (20 mg/kg at the rate of 100 mg/min IV)

D: IV LEV (25 mg/kg over 15 min IV)

E: IV LEV + CNP (2.5 g for 5 min IV)

F: IV LEV (30 mg/kg over 30 min IV) | A: VPA (30 mg/kg at the rate of 5 mg/kg/min)

B: LOR (0.1 mg/kg over 2–4min)

C: PHT (20 mg/kg with max rate of 50 mg/min)

D: VPA (30 mg/kg over 15 min IV) vs. (PHT 20 mg/kg over 20 min)

E: placebo + CNP (placebo for 5 min co-intervention: IV CNP 1 mg for 1 min)

F: PHT (20 mg/kg over 30 min co-intervention: IV LOR 4 mg or DZP 5–10 mg over 2 min)

| End-point of follow-up: Time not reported.

A: during hospital stay. B: during hospital stay. C: during hospital stay. D: 1mo after hospital discharge. E: during hospital stay. F: during hospital stay.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N.R.

| Outcome measure 1: Drug administration to seizure cessation (critical) Definition not reported (‘Clinical seizure cessation after drug administration’). *IV LEV vs. IV LOR: N.R. *IV LEV + CNP vs. IV placebo + CNP: N.R.

*IV LEV vs. IV PHT C: 0.87 [95%CI 0.55 to 1.36] D: 1.15 [95%CI 0.90 to 1.46] F: 1.12 [95%CI 0.83 to 1.49] Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.09 [95%CI 0.92 to 1.29], favoring IV PHT. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

* IV LEV vs. IV VPA A: 1.08 [95%CI 0.79 to 1.47] D: 1.15 [95%CI 0.90 to 1.46] Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.12 [95%CI 0.93 to 1.36], favoring IV VPA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure 2: termination of SE after drug administration (critical) Defined as termination of SE after drug administration (within 10min, 15min, or 24h). *IV LEV vs. IV PHT: N.R. *IV LEV vs. IV VPA: N.R.

* IV LEV vs. IV LOR: B Within 10min à LEV: 29/38 vs. lorazepam: 31/41, p=1.00 Within 24h à LEV: 23/29 vs. LOR: 21/31, p=0.38

*IV LEV + CNP vs. IV placebo + CNP: E Within 15min à LEV: 57/68 vs. placebo: 50/68, RR=0.88 [95%CI 0.71 to 1.05], p= 0.14.

Outcome measure 3: mortality (important) Defined as in hospital mortality. *IV LEV vs. IV LOR: N.R. *IV LEV + CNP vs. IV placebo + CNP: N.R.

* IV LEV vs. IV PHT C: 1.00 [95%CI 0.15 to 6.48] D: 0.83 [95%CI 0.27 to 2.55] F: 0.91 [95%CI 0.17 to 4.99] Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 0.88 [95%CI 0.38 to 2.04], favoring IV LEV. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

*IV LEV vs. IV VPA A: 1.00 [95%CI 0.15 to 6.76] D: 0.83 [95%CI 0.27 to 2.55] Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.17 [95%CI 0.41 to 3.34], favoring IV VPA. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure 4: requirement for ventilatory support (important) Defined as use assisted breathing.

* IV LEV vs. IV LOR: B LEV: 4/38 vs. lorazepam: 10/41, p=0.03

*IV LEV vs. IV PHT: N.R. *IV LEV vs. IV VPA: N.R. *IV LEV + CNP vs. IV placebo + CNP: N.R. | Facultative: Results suggested that IV LEV was comparable to IV PHT, VPA, or LOR in efficacy, and IV LEV + CNP had no superiority in seizure cessation than CNP + placebo. IV LEV may have a better tolerability than other AEDs do.

Limitations: * Only studies published in journals or in certain trial registers were included. * Included trials varied in terms of trial design, type of comparator drugs, and outcomes. Might be underpowered. * Almost all SE patients had a conscious disturbance during the episode à it was sometimes difficult to obtain informed consent. * The number of included studies and participants was limited and might be underpowered. * Follow-up period of the included studies was relatively short. * Adverse events were not assessed. *Navarro: higher doses of benzodiazepines, lower thresholds for determining cessation of SE, 23% patients excluded due to absence of legally required consent. à likely masked (high risk of bias).

Sensitivity analyses: Random-effects model was converted to fixed-effects model, and RR value was transformed into OR. The research conclusions were consistent, indicating that the results of the meta-analysis were stable.

Heterogeneity: No statistically significant heterogeneity was found for all pooled analysis. |

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Intervention (I) | Comparison / control (C) | Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments |

Kobata, 2020

PS. Study characteristics and results are extracted from the SR. | SR and meta-analysis of RCTs.

Literature search up to September 2019.

A: Leppik, 1983 B: Alldredge, 2001

A: RCT B: RCT

Setting and Country: A: USA B: USA

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: non-commercial / industrial co-authorship

| Inclusion criteria SR: * RCTs in humans published before September 2019. * Adult SE patients in an emergency setting, including prehospital care. * Studies written in English or Japanese.

Exclusion criteria SR: N.R.

2 studies included

Important baseline patient characteristics: No. of patients A: 37 vs. 33 B: 66 vs. 68

Mean age ± SD A: 50 vs. 56 B: 49.9 vs. 50.4

Definition of SE and inclusion criteria A: Convulsive SE (defined as ≥3 GTC seizures in 1h or ≥2 in rapid succession), absence SE, or complex partial SE B: Continuous or repeated seizure activity >5 min without recovery of consciousness

Sex (M/F) N.R.

SE type N.R.

Groups comparable at baseline? Yes. | A: LOR 4 mg IV B: LOR 2 mg IV

| A: DZP 10 mg IV B: DZP 5 mg IV | End-point of follow-up: N.R.

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? N.R.

| Outcome measure 1: Drug administration to seizure cessation (critical) *LEZ vs. DZP Effect measure: RR [95% CI] A: 1.39 [95%CI 0.94 to 1.47] B: 1.18 [95%CI 0.9 to 1.95]

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.24 [95%CI 1.03 to 1.49], favoring IV LEZ. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure 2: termination of SE after drug administration (critical) N.R.

Outcome measure 3: mortality (important) Defined as mortality at discharge.

*LEZ vs. DZP Effect measure: RR [95% CI] A: not estimable B: 1.72 [95% CI 0.43 to 6.90],

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.72 [95% CI 0.43 to 6.90], favoring IV DZP. Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable.

Outcome measure 4: requirement for ventilatory support (important) *LEZ vs. DZP Effect measure: RR [95% CI] A: 0.89 [95%CI 0.24 to 3.29] B: 1.20 [95%CI 0.43 to 3.39]

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 1.07 [95%CI 0.48 to 2.41], favoring DZP. Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure 5: hypotension (important) *LEZ vs. DZP Effect measure: RR [95% CI] A: 2.68 [95%CI 0.11 to 63.71] B: N.R.

Pooled effect (random effects model): RR 2.68 [95%CI 0.11 to 63.71], favoring DZP. Heterogeneity (I2): not applicable. | Facultative: The results of this meta-analysis of RCTs showed that i.v. LOR was better than i.v. DZP for the cessation of adult SE.

Limitations: * Underlying aetiology and the duration of SE before benzodiazepine treatment were not clarified. * Lack of uniform definitions of SE.

Sensitivity analyses: N.R.

Heterogeneity: No statistically significant heterogeneity was found for all pooled analysis. |

N: number of patients; M/F: male/female; SE: Status Epilepticus; N.R: Not reported; LEV: levetiracetam; DZP: diazepam, PHT: phenytoin; VPA: valproate; LOR: lorazepam; CNP: clonazepam; GCSE: generalized convulsive status epilepticus.

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies

| Study reference | Study characteristics | Patient characteristics | Intervention (I) | Comparison / control (C)

| Follow-up | Outcome measures and effect size | Comments | |

| Kapur, 2019 | Type of study: RCT

Setting and country: USA