Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen bij PFP

Uitgangsvraag

Wat is de waarde van aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen (tapen, brace en zolen) bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn?

Aanbeveling

Behandel patellofemorale pijn in eerste instantie alleen door middel van oefentherapie gedurende zes tot twaalf weken (zie de module Oefentherapie PFP).

Overweeg tape, brace of zolen in aanvulling op oefentherapie indien oefentherapie alleen niet het gewenste resultaat heeft.

Informeer de patiënt over gebrek aan bewezen effectiviteit van de aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen en beslis samen over eventueel aanvullende behandelingen.

Overwegingen

Voor- en nadelen van de interventie en de kwaliteit van het bewijs

Taping

Op basis van de literatuursamenvatting lijkt een behandeling met tape, aanvullend op oefentherapie, geen klinisch relevant effect te hebben op de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en functie. Het effect op functie na zes weken is onduidelijk. De lage tot zeer lage bewijskracht wordt met name veroorzaakt door beperkingen in de opzet van de studies en kleine aantallen patiënten. Er ligt hier dan ook een kennislacune. Belangrijke uitkomstmaten terugkeer naar sport/werk, tevredenheid en herstel kunnen geen verdere bijdrage leveren aan de richting van de besluitvorming. Ten aanzien van deze uitkomstmaten werd geen literatuur geïncludeerd in de samenvatting.

Kniebraces

Op basis van de literatuursamenvatting is het onduidelijk of een behandeling met een kniebrace, aanvullend op oefentherapie, effect heeft op de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en functie vanwege de zeer lage bewijskracht. Deze zeer lage bewijskracht wordt met name veroorzaakt door beperkingen in de opzet van de studies en kleine aantallen patiënten. Er ligt hier dan ook een kennislacune. Belangrijke uitkomstmaten terugkeer naar sport/werk, tevredenheid en herstel kunnen geen verdere bijdrage leveren aan de richting van de besluitvorming. Ten aanzien van deze uitkomstmaten werd geen literatuur geïncludeerd in de samenvatting.

Zolen

Op basis van de literatuursamenvatting is het onduidelijk of een behandeling met zolen, aanvullend op oefentherapie, effect heeft op de cruciale uitkomstmaten pijn en functie vanwege de zeer lage bewijskracht. Deze zeer lage bewijskracht wordt name veroorzaakt door beperkingen in de opzet van de studies en kleine aantallen patiënten. Er ligt hier dan ook een kennislacune. Belangrijke uitkomstmaten terugkeer naar sport/werk, tevredenheid en herstel kunnen geen verdere bijdrage leveren aan de richting van de besluitvorming. Ten aanzien van deze uitkomstmaten werd geen literatuur geïncludeerd in de samenvatting.

Voor het gebruik van tape, zolen en braces wordt in de literatuur geen bijwerkingen of complicaties gevonden ten opzichte van de controlegroep. Allergische en niet-allergische dermatitis ten gevolge van taping is wel beschreven. De werkgroep is van mening dat op basis van de literatuur deze interventies vrijwel geen nadelige bijwerkingen sorteren.

Vanuit de ‘Patellofemoral pain clinical practice guideline’ (Willy, 2019), wordt interventie middels individueel afgestemde tape en/of zolen aangeraden bij 1) aanwezigheid van statische valgisatie van de voet en/of 2) dynamische overpronatie of vergrote mobiliteit van de voet, in combinatie met oefentherapie voor verlichting van pijn op de korte termijn. Braces worden in deze guideline niet geadviseerd, omdat deze geen pijnreductie geven.

Uit onze literatuurstudie komen deze adviezen en effecten niet naar voren. De in de richtlijn beschreven literatuurstudies gaan over groepen patiënten, welke niet op specifieke individuele kenmerken (zoals biomechanische afwijkingen in stand of functie) geselecteerd zijn. De achterliggende gedachte achter aangemeten zolen is dat ook hier een beoordeling van de individuele biomechanica wordt gemaakt (zoals aanwezigheid van statische valgisatie van de voet, dynamische overpronatie of vergrote mobiliteit van de voet) waarbij de zolen de biomechanica kan beïnvloeden. Een recente klinische trial (Matthews, 2020) toont echter aan dat de groep patiënten met een vergrote midvoet mobiliteit (als maat voor hyperpronatie) en die een ondersteunende zool gebruikt geen betere resultaten laat zien dan de groep patiënten die heup-oefeningen uitvoert voor patellofemorale pijn.

De werkgroep sluit niet uit dat personalisatie van de behandeling op basis van diverse biomechanische variabelen samen met een oefenprogramma in de praktijk tot klinische resultaten kan leiden.

Een veel geciteerd artikel over de aanvullende effecten van zolen op oefentherapie bij patellofemorale pijn is dat van Collins (2008). Deze studie vindt alleen op het domein ‘recovery’ een significant verschil na 6 weken tussen ‘insoles’ (op maat gemaakte zolen) en ‘flat inserts’ (kant-en-klare zolen). Hierbij scoren de ‘insoles’ beter dan de ‘flat inserts’. Op het pijndomein wordt op geen enkel meetpunt significante verschillen gevonden tussen de verschillende interventies (insoles, flat inserts en fysiotherapie). Hoewel vroege resultaten voor globale verbetering gunstig waren voor de zolen was dit effect niet meer zichtbaar na 12 weken en 52 weken.

In de praktijk wordt vooral het aanleggen van tape rondom de knieschijf gezien als een methode om op directe wijze pijn te verminderen en functie te verbeteren. Ook het aanmeten van zolen vindt geregeld plaats in de praktijk. De werkgroep realiseert zich dat deze toepassing in de klinische setting plaatsvindt, hoewel het bewijs ervoor ontbreekt. Bij tapen is het niet uitgesloten dat geobserveerde verbeteringen berusten op een placebo-effect.

In de studie van Akbas (2011) hebben de patiënten een gemiddeld hoge(re) leeftijd; de werkgroep is van mening dat deze studie mogelijk niet over patellofemorale pijn gaat. Aangezien er weinig verschil uit de studie naar voren komt, zijn de effecten uiteindelijk verwaarloosbaar op de uitkomsten voor deze richtlijn.

We hebben ons in deze richtlijn geconcentreerd op de AKPS/Kujala score, omdat deze hoofdzakelijk worden gebruikt in de literatuur voor het meten van pijnscore. Andere scores (KOOS/WOMAC en Tegner) zijn niet gevalideerd voor patellofemorale pijn maar wel gevonden in enkele literatuurstudies. Deze hebben geen afkappunt voor patellofemorale pijn; een ‘minimal clinical important difference’ voor sport of werkhervatting wordt in de Tegner score, KOOS of WOMAC niet gedefinieerd, ook niet voor tevredenheid en herstel.

Uboldi (2018) rapporteert aantallen terugkerende sporters maar gebruikt hierbij geen Tegner score. Petersen (2016) gebruikt het domein ‘sports en recreational activities’ in de KOOS als score; ook hiervan zijn geen afkapwaarden bekend en zijn deze niet gevalideerd voor patellofemorale pijn.

Waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten (en eventueel hun verzorgers)

Om meer inzicht te krijgen in de waarden en voorkeuren van patiënten met patellofemorale pijn is er in samenwerking met Patiëntenfederatie Nederland een vragenlijst opgesteld en uitgezet. De vragenlijst werd ingevuld door 43 patiënten met patellofemorale pijn (21 die het hebben gehad en 22 die het momenteel hebben). 75% van de respondenten gaf aan een aanvullende behandeling te hebben ontvangen zoals zolen, tape of een brace.

Patiënten willen het liefst (zo snel mogelijk) weer normaal kunnen functioneren in het dagelijks leven, daarnaast wordt werk hervatten en de sportbelasting zoals voorheen kunnen doen als belangrijk ervaren.

In de reacties op deze vragenlijst worden een aantal voor- en nadelen genoemd met betrekking tot aanvullende behandeling.

Tape

Het gemak van het dragen van tape werd als voordeel benoemd. Het geeft meer stabiliteit en ontlasting van pijnlijke spieren. Het geeft meer vertrouwen in het belasten van de knie bij de respondenten. Echter, langdurig gebruik van tape kan aanleiding geven tot beschadiging van de huid; mogelijk dat er lijmresten achter blijven op de huid na het verwijderen van tape. Respondenten ervaren dat zij afhankelijk zijn van een fysiotherapeut om tape aan te leggen als een nadeel; bij sommige respondenten gaat tape snel los en niet alle respondenten hebben pijnverlichting ervaren.

Brace

Het voordeel van de brace was dat het beweging beperkt en rust geeft, respondenten gaven aan dat het helpt bij het uitstellen van een operatie. De braces zijn zichtbaar voor anderen, dat roept vragen op uit de omgeving dat vinden niet alle respondent prettig. Een aantal respondenten ervaren de brace als lomp en zwaar, bovendien werd het feit dat de knie altijd gestrekt bleef als onprettig ervaren. Niet alle respondenten hebben effecten waargenomen van de brace.

Zolen

De zolen werden als gemakkelijk in gebruik ervaren, respondenten hoeven er niet aan te denken en het verbeterde de stand van de voet en het been van de respondenten, ook zorgen de zolen voor meer stabiliteit en pijnreductie. Een nadeel van zolen is dat kosten vaak maar deels vergoed worden door de verzekeraar; respondenten geven aan dat ze beperkt zijn in hun schoenkeuze en niet alle respondenten hebben effecten waargenomen van de zolen.

De patiënt wil graag geïnformeerd worden over de verschillende behandelmogelijkheden, de voor- en nadelen van deze aanvullende behandelingen, het klachtenverloop en het behandeltraject. Het hebben van goed contact met de zorgverlener en de nazorg bij de behandeling zijn van grote invloed op hoe de behandeling wordt ervaren.

Tevredenheid over behandeling:

- Tape: 50% van de respondenten is tevreden of zeer tevreden en 10% zeer ontevreden.

- Brace: 3 respondenten kozen voor een brace; een respondent is tevreden, één ontevreden één neutraal.

- Zolen: 54% van de respondenten is hierover tevreden of zeer tevreden, 18% is ontevreden.

Kosten (middelenbeslag)

Aan het vervaardigen van een aangemeten brace en zolen zijn kosten verbonden. Er is geen economische analyse beschikbaar over de kosten van deze hulpmiddelen, noch of deze opwegen tegen de baten (kosteneffectiviteit). Het is daardoor voor de werkgroep niet mogelijk een uitspraak te doen over deze kosten. Globaal kan worden gesteld dat de kosten van tape en kant-en-klare braces en zolen laag zijn (€20 tot €50). Aangemeten braces en zolen zijn gebruikelijk duurder (uiteenlopend van €100 tot €250). Hoewel de kosten relatief laag zijn en vaak deels worden vergoed, is de werking van aanvullende behandelingen onduidelijk. Vanuit dit standpunt dient de patiënt een persoonlijke afweging te maken alvorens te starten met aanvullende behandeling(en).

Aanvaardbaarheid, haalbaarheid en implementatie

Conservatieve behandelingen, zoals tapen, braces en zolen, worden in de klinische praktijk al veelvuldig toegepast. Mogelijke bezwaren die vanuit het werkveld kunnen komen is dat niets gestandaardiseerd is. Goede kennis van wat je medebehandelaars kunnen en doen is essentieel in goede besluitvorming over het inzetten van aanvullende behandeling. Hiervoor is een uitgebreid goed werkend/communicerend multidisciplinair netwerk noodzakelijk.

Bezwaren welke kunnen worden ingebracht door de patiënt liggen waarschijnlijk vooral in de kosten. Hoewel deze relatief laag zijn heeft niet iedereen de financiële mogelijkheid om zolen te bekostigen of een aanvullende verzekering die de kosten (gedeeltelijk) dekt. De genoemde aanvullende behandelingen worden vooralsnog niet vanuit de basisverzekering vergoed. Daarnaast zijn de vergoedingen per verzekeraar en aanvullend verzekeringspakket verschillend, waarbij niet altijd het gehele bedrag wordt vergoed, maar slechts een deel. De patiënt wil graag geïnformeerd worden over de voor- en nadelen van de conservatieve behandelingen.

Er zijn volgens de werkgroep voldoende zorgverleners in Nederland om te voorzien in individueel aangemeten tape, brace en zolen.

Rationale van de aanbeveling: weging van argumenten voor en tegen de interventies

Door een gebrek aan bewijs en deels conflicterende uitkomsten worden tape, brace of zolen bij patellofemorale klachten niet opgenomen als aanbeveling voor primaire behandeling van PFP. Deze behandelingen kunnen wel worden ingezet als aanvulling/secundaire therapie op oefentherapie.

Onderbouwing

Achtergrond

In de praktijk worden er veel verschillende conservatieve behandelingen toegepast bij patellofemorale pijn. Deze conservatieve behandelingen zijn veelal opgebouwd uit oefentherapie in combinatie met diverse aanvullende behandelingen en richten zich op pijnvermindering en/of functieverbetering. In de Engelstalige literatuur wordt dit ook wel ‘multimodal treatment’ genoemd. In de literatuur worden deze vaak als gecombineerde interventie beschreven. Er is geen eenduidigheid wat de waarde is van aanvullende behandelingen op herstel van patellofemorale pijn. Welke behandelingen een positieve aanvulling kunnen geven op het effect van oefentherapie en wat verwacht kan worden op de korte en lange termijn ter verbetering van patellofemorale pijn is hierin tevens niet duidelijk. De drie meest toegepaste aanvullende behandelingen zijn; taping, bracing van de knie en zolen. In de literatuur is gezocht naar combinatie van een voorgenoemde behandeling met oefentherapie en op zichzelf staand als enkelvoudige behandeling. Andere conservatieve behandelvormen zoals rekken/ketenlenigheid, dry needling en shockwave zijn in deze richtlijnmodule niet meegenomen.

Conclusies

Question 1: Taping

|

Low GRADE |

The addition of taping to an exercise program may have no effect on pain in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Sources: (Akbas, 2011; Arrebola, 2020; Callaghan, 2012; Begum, 2020; Ghourbanpour, 2018; Gunay, 2017) |

|

Low GRADE |

The addition of taping to an exercise program may have no effect on function in patients with patellofemoral pain after six weeks intervention.

Sources: (Akbas, 2011; Arrebola, 2020; Gunay, 2017) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear what the effect of the addition of taping to an exercise program is on function in patients with patellofemoral pain during follow-up (six weeks post-intervention).

Sources: (Akbas, 2011; Arrebola, 2020) |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures return to work/sport, patient satisfaction and recovery in patients with patellofemoral pain were not reported in the included studies. |

Question 2: Braces/knee orthosis

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether the addition of bracing to an exercise program has an effect on pain in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Sources: (Alsharani, 2019; Petersen, 2016; Smith, 2015; Uboldi, 2017) |

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether the addition of bracing to an exercise program has an effect on function in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Sources: (Alsharani, 2019; Petersen, 2016; Smith, 2015; Uboldi, 2017) |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures return to work/sport and patient satisfaction in patients with patellofemoral pain were not reported in the included studies. |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether the addition of bracing to an exercise program has an effect on patient recovery in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Sources: (Petersen, 2016) |

Question 3: Insoles/foot orthosis

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether the addition of insoles to an exercise program has an effect on pain in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Sources: (Hossain, 2011) |

|

Very low GRADE |

It is unclear whether the addition of insoles to an exercise program has an effect on function in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Sources: (Hossain, 2011) |

|

- GRADE |

The outcome measures return to work/sport, patient satisfaction and recovery in patients with patellofemoral pain were not reported in the included studies. |

Samenvatting literatuur

Question 1: Taping

Description of studies

Calaghan (2012) is a Cochrane review that included meta-analyses of the effect of knee-taping and exercises (n=50; age and gender not reported) compared with exercises (mostly stretching and strengthening lower limbs) alone (n=50; age and gender not reported) on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain. Three included RCTs were relevant for the current literature review. Different taping techniques (see evidence table) were used in each study. In Clark (2000), both groups also received education and in Tunay (2003), both groups also received treatment with ice in addition to the described interventions above. In Wittingham (2004) groups did not receive additional interventions besides taping and exercises, but a placebo taping with exercises group besides the exercise only control group was included as well. Meta-analyses were performed for outcome measures at the end of treatment (three weeks to three months).

Arrebola (2020) studied the effect of two KT® taping techniques (see evidence table) in combination with exercises (technique 1: n=13, age (SD)=30.4(8.4) years; technique 2: n=14, age (SD)=27.9 (9.4) years) compared to exercises (hip and quadriceps strengthening) alone (n=16, age (SD)=30.3 (7.9)) on pain and function in females with patellofemoral pain. The treatment period was 12 weeks.

Begum (2020) studied the effect of the McConnel taping technique in combination with exercises (n=16) compared to exercises (strengthening m. vastus medialis) alone (n=25) on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain. Patients were 36.0 (SD=7.4) years old. The treatment period was two weeks.

Ghourbanpour (2018) studied the effect of the McConnell taping technique in combination with exercises (n=15, age (SD)=33.9(10.3) years, gender not reported) compared to exercises (strengthening m. vastus medialis oblique, stretching hamstring muscles and iliotibial band and patellar mobilization) alone (n=15, age (SD)=37.2(12.4) years, gender not reported) on pain and function in patients with anterior knee pain. The treatment period was four weeks.

Gunay (2017) studied the effect of kinesio taping in combination with exercises (n=25 knees age (SD)=36.0(8.0) years, 31.3% male) compared to sham taping with exercises (n=25 knees, age (SD)=31.7(8.5) years, 50% male) and no exercises (strengthening quadriceps, m. gluteus medius, stretching quadriceps, hamstring and gastrocnemius muscles and iliotibial band) alone (n=25 knees, age (SD)=33.8(6.7) years, 61.5% male) on pain and function in patients with anterior or retropatellar knee pain. The treatment period was six weeks.

Akbas (2011) investigated the effect of kinesio taping in combination with exercises (n=15, age (SD)=41.0(11.3) years) compared to exercises (muscle strengthening and soft tissue stretching) alone (n=16, age (SD)=44.9(7.8) years) on pain in female patients with patellofemoral pain. The treatment period was six weeks.

Results

Pain

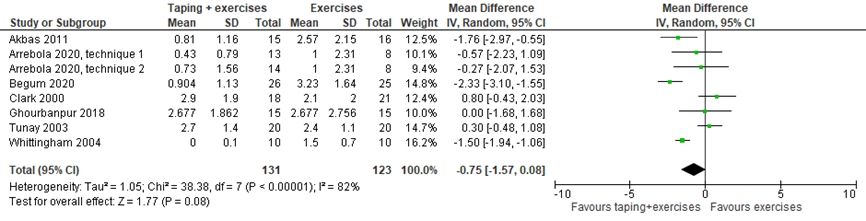

Callaghan (2012) performed a meta-analysis of pain VAS-score after treatment period. As all additional selected RCTs reported pain VAS-scores and numerical pain rating scores (NPRS), we extended this meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of taping in addition to exercises on pain-scores after the treatment period (see figure 1). Gunay (2017) could not be included in meta-analysis as only median(range)-scores (I: VAS (range)=30(0-50), n=25 knees; C: VAS (range) = (20(0-40), n=25 knees) values were reported. In both the meta-analysis and Gunay (2017), for post-intervention measures, no statistically significant nor clinically relevant effect of taping as an addition to exercise therapy (MD (95%CI): -0.75(-1.57, 0.08), favoring tape)) on pain was found.

Figure 1 Pain scores after treatment period

Three studies (see table 1) evaluated the results on the long-term. No statistically significant nor clinically relevant differences in pain scores between groups were found (table 1). Due to heterogeneity in follow-up periods (see table 1) and limited reporting (for example Gunay (2017)), data could not be pooled.

Table 1 Pain scores after taping and follow-up period

|

|

MD (95%CI) |

n |

Follow-up, after ending treatment |

|

Arrebola 2020, |

-0.70 (-2.09, 0.69) |

I: 13 |

6 weeks |

|

Clark 2000, |

-0.13 (-0.96, 3.52) |

I: 10 |

9 months |

|

Gunay 2017, |

-10 (not reported) |

I: 25 knees |

6 weeks |

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded to low because of:

- study limitations (1 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables);

- low number of participants (1 level, imprecision).

Function

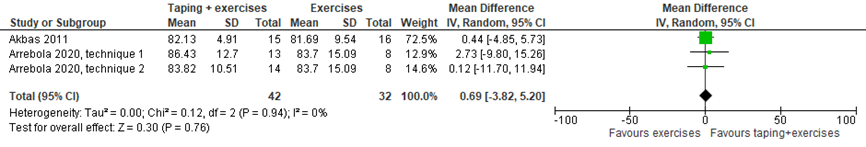

Several studies (Akbas, 2011; Arrebola, 2020; Gunay, 2017) evaluated the additional effect of taping to an exercise program on function using the Kujala Anterior Knee Pain Scale (see evidence tables). A meta-analysis was performed (Figure 2). Gunay (2017) could not be included in meta-analysis as only median(range)-scores were reported (I: Kujala median(range)=87 (74 to 100), n=25 knees; C: Kujala median (range) =87(82 to 94)), n=25 knees, difference was not statistically significant nor clinically relevant). Taping in combination with exercises did not result in statistically significant nor clinically relevant improved function after six weeks intervention when compared to exercises alone, MD (95%CI): 0.69(-3.82, 5.20).

Figure 2 Function in the short-term (6 weeks)

After a follow-up period, two studies (see Table 2), investigated the difference in function after treatment with tape and exercises compared to exercises alone as well. Due to not reporting mean (SD) values (for example Gunay (2017)), data could not be pooled. Conflicting results regarding the effect of taping as an addition to exercise therapy were reported.

Table 2 Function scores after taping and follow-up period

|

|

MD (95%CI) |

n |

Follow-up, after ending treatment |

|

Arrebola 2020, |

12.50 (2.90, 22.10), favoring tape |

I: 13 |

6 weeks |

|

Arrebola 2020, |

12.20 (1.91, 22.49), favoring tape |

I: 13 |

6 weeks |

|

Gunay 2017, |

-1 (not reported) |

I: 25 knees |

6 weeks |

Level of evidence of the literature

Function short-term (after six weeks intervention)

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded to low because of:

- study limitations (1 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables);

- low number of participants (1 level, imprecision).

Function follow-up six weeks

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded to very low because of:

- study limitations (1 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables);

- conflicting study results (1 level, inconsistency);

- low number of participants (1 level, imprecision).

Return to sport/work

Return to sport/work was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to sport/work was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient satisfaction was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Patient recovery

Patient recovery was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient recovery was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Question 2: Braces/knee orthosis

Description of studies

Smith (2015) is a Cochrane review which included meta-analyses evaluating the effect of treatment of knee orthosis (sleeve and Special FX knee brace) and exercises compared with exercises (mostly stretching and strengthening lower limbs) alone on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain. Two RCTs were relevant for the current literature review (Lun, 2005; Evcik, 2010). Together, these studies included 104 patients in three intervention groups (mean age (SD)respectively: 42.2 (15.3) years, 35 (11) years and 35 (9) years; % male/female not reported) and 79 patients in two control groups (mean ages (SD): 41.0(9.3) years, 35(11); % male/female not reported). Based on follow-up periods, treatment duration ranged from 6 to 12 weeks.

Alsharani (2019) studied the effect of a knee brace (brace set to resist knee flexion) in combination with exercises (n=21, age (SD)=30.8(5.6) years, 42.9% male) compared to exercises alone (specific exercises that are part of the protonic therapy program; for control group, the brace was replaced with a sport cord; n=20, age (SD)=26.7(3.0) years, 60% male) on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain. The treatment period was four weeks.

Uboldi (2018) studied the effect of a knee brace (Reaction Knee Brace; DJO Global, Vista, California, United states) in combination with exercises compared to exercises (rehabilitation protocol) alone on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain. 60 patients (30 in each group) were analysed and had a mean age (SD) of 20(4) years. A total of 22% was male. The treatment period was not defined.

Petersen (2016) studied the effect of a knee brace (Patella Pro) in combination with exercises (n=78, age (SD)=28.0(9.4) years, 34.2% male) compared to exercises alone (home based exercise program; n=78, age (SD)=28.0(8.1) years, 21.1% male) on pain and function in patients with anterior knee pain. The treatment period was six weeks.

Results

Pain

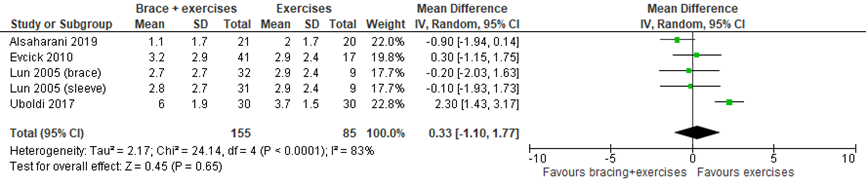

Smith (2015) performed a meta-analysis of reported VAS pain scores. As two additional RCTs reported pain VAS-scores and numerical pain rating scores (NPRS) as well, we extended this meta-analysis to investigate the effect of bracing in addition to exercises on pain-scores after the treatment period (see figure 3). No significant and clinically relevant effect of bracing as an addition to exercise therapy (MD (95%CI): 0.33(-1.10, 1.77), favoring exercises alone)) on pain was found when treatment period was finished.

Petersen (2016) could not be included in the meta-analysis as results were only reported in figures and narrative text. In this study, inconsistent results were noted for pain after six and twelve weeks wearing the brace. During climbing stairs or playing sports, but not during walking and rest, a significant decrease in pain for the group wearing the brace compared to the control group was found.

Figure 3 Pain in the short-term (≤12 weeks)

Uboldi (2018) and Petersen (2016) reported pain scores after a follow-up period. Peterson (2016) reported no significant differences in pain scores between groups after 1 year starting treatment (values not reported). However, Uboldi did report statistically significant differences in pain scores after six (MD (95%CI): -1.60 (-2.38, -0.82)) and twelve months (MD (95%CI): -0.9 (1.69, -0.11)) in favor of bracing. However, these differences are deemed not clinically relevant.

Level of evidence of the literature

Pain

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded three levels to very low because of:

- study limitations (2 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables and Smith (2015));

- low number of participants (1 level, imprecision).

Function

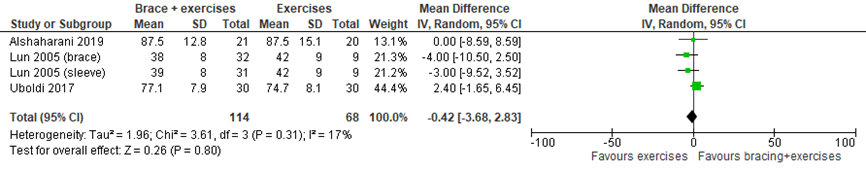

Smith (2015) performed a meta-analysis of reported functional scores using the post-intervention scores. One study used the Kujala Knee Pain Score (Lun, 2005). As the additional RCTs reported post-intervention knee function scores as well, we extended this meta-analysis (see Figure 4). Petersen (2016) could not be included as the results were only reported in figures and narrative text. They found significantly improved Kujala scores after six and twelve weeks for the group receiving a brace in addition to exercises when compared to the scores of the group receiving only exercises.

In the meta-analysis, no statistically significant nor clinically relevant effect of bracing in addition to exercise therapy was found on function (MD (95%CI): -0.42(-3.68, 2.83), favoring exercises alone).

Figure 4 Function (kujala knee pain score) after bracing in the short term

On the long-term, only Uboldi (2018) investigated the added value of a brace to exercise therapy regarding function with the Kujala scale. No statistically significant nor clinically relevant effect was found at 6 months (MD (95%CI): 2.90 (-1.05, 6.85)) and 12 months (MD (95%CI: 2.50 (-1.50, 6.50)).

Level of evidence of the literature

Function

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded to very low because of:

- study limitations (2 levels, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables);

- low number of participants (1 level, imprecision).

Return to sport/work

Return to sport/work was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to sport/work was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient satisfaction was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Patient recovery

Petersen (2016) reported no statistically significant difference between groups in proportions of patients reporting recovery. As values were not reported, clinical relevance could not be determined.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded very low because of:

- study limitations (1 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables);

- low number of studies and not reporting confidence intervals (2 levels, imprecision).

Question 3: Insoles/foot orthosis

Description of studies

Hossain (2011) is a Cochrane review investigating the effect of foot orthosis and exercises (n=54) compared with exercises alone (n=55) on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain. Patient characteristics were not reported per group. Duration of treatment was not for all studies clearly described. Based on follow-up periods, treatment duration ranged from 4 to 8 weeks, but treatment could be continued unsupervised.

Results

Pain

Hossain (2011) reported effect of treatment on VAS in one RCT (Collins, 2008; see table 3). Adding foot orthosis did not have a statistically significant nor clinically relevant effect on pain in patients with patellofemoral pain.

Table 3 pain scores after treatment with insoles

|

|

MD (95%CI) |

n |

|

Collins 2008, |

-3.7 (-12.99, 5.59) |

I: 42 |

|

Collins 2008, |

-3.4 (-13.52, 6.72) |

I: 43 |

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded to very low because of:

- study limitations (1 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables and Hossain, 2011);

- low number of participants (2 levels, imprecision).

Function

Hossain (2011) reported effect of treatment the Kujala anterior knee pain scale. Foot orthosis did not have a statistically significant nor clinically relevant additional effect to exercises on pain in patients with patellofemoral pain (see table 4).

Table 4 function scores after treatment with insoles

|

|

MD (95%CI) |

N |

|

Collins 2008, |

0.2 (-3.72, 4.12) |

I: 42 |

|

Collins 2008, |

3.6 (-0.52, 7.72) |

I: 43 |

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence of RCTs starts at high, but was downgraded to very low because of:

- study limitations (1 level, risk of bias, see risk of bias tables and Hossain, 2011);

- low number of participants (2 levels, imprecision).

Return to sport/work

Return to sport/work was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome return to sport/work was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Patient satisfaction

Patient satisfaction was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient satisfaction was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Patient recovery

Patient recovery was not described as an outcome in the included studies.

Level of evidence of the literature

The level of evidence regarding the outcome patient recovery was not assessed due to lack of studies.

Zoeken en selecteren

Question 1: taping

What is the efficacy of taping in combination with exercises when compared to exercises alone in patients with patellofemoral pain?

P: patients with patellofemoral pain (adolescents/adults, non-traumatic);

I: taping in combination with exercises;

C: exercises alone (same as intervention);

O: pain, mobility/function, return to sport/work, patient satisfaction, patient recovery.

Question 2: knee orthoses

What is the efficacy of bracing (knee orthoses) in combination with exercises when compared to exercises alone in patients with patellofemoral pain?

P: patients with patellofemoral pain (adolescents/adults, non-traumatic);

I: bracing/knee orthoses in combination with exercises;

C: exercises alone (same as intervention);

O: pain, mobility/function, return to sport/work, patient satisfaction, patient recovery.

Question 3: foot orthoses/insoles

What is the efficacy of insoles (foot orthoses) in combination with exercises when compared to exercises alone in patients with patellofemoral pain?

P: patients with patellofemoral pain (adolescents/adults, non-traumatic);

I: foot orthoses/insoles in combination with exercises;

C: exercises alone (same as intervention);

O: pain, mobility/function, return to sport/work, patient satisfaction, patient recovery.

Relevant outcome measures

The guideline development group considered pain and function as a critical outcome measures for decision making; and return to sport/work, patient satisfaction and patient recovery as important outcome measures for decision making.

For the outcome pain the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) were used. For the outcome function Kujala score/ Anterior Knee Pain Score (AKPS) are used. Return to sport/work was measured with the Tegner score. Satisfaction with the result of treatment and recovery were usually measured on a Likert scale.

The working group defined a difference of 2 cm (out of 10 cm) on the VAS or NRS scale as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference for pain, in line with Crossley, 2004. For the Kujala score/ AKPS score regarding function, a difference of 10 point (out of 100 points) was defined as a minimal clinically (patient) important difference, in line with Crossley, 2004. In case pooling of the results of individual studies was indicated and the studies used different functional scores, a standardized mean difference of 0.5 was used. A minimal clinically important difference for return to sport/work, patient satisfaction and patient recovery was not predefined.

Search and select (Methods)

For all PICO’s together, the databases Medline (via OVID) and Embase (via Embase.com) were searched with relevant search terms until April 28th 2020. The detailed search strategy is depicted under the tab Methods. The systematic literature search resulted in 475 hits. Studies were selected based on the following criteria:

- systematic review (including evidence tables, risk of bias assessments, published in 2010 or later) or RCT (published in 2000 or later);

- including patients with patellofemoral pain, excluding Osgood-Schlatter syndrome, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome, Iliotibial band syndrome, osteoarthritis;

- comparing treatment with tape, braces/knee orthoses or insoles/foot orthoses in combination with exercise therapy, with exercise therapy alone.

Eighty-tree studies were initially selected based on title and abstract screening and checking references from relevant reviews. After reading the full text, 65 studies were excluded (see the table with reasons for exclusion under the tab Methods), and 18 studies (3 systematic reviews and 15 RCTs from which 7 were included in systematic reviews as well) were included.

Results

Regarding taping, one systematic review (including three RCTs meeting inclusion criteria) and five additional RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Regarding braces/knee orthoses, one systematic review (including two RCTs meeting inclusion criteria) and three additional RCTs were included in the analysis of the literature. Regarding insoles/foot orthoses, one systematic review (including one RCT meeting inclusion criteria) was included in the analysis of the literature. Important study characteristics and results are summarized in the evidence tables. The assessment of the risk of bias is summarized in the risk of bias tables.

Referenties

- Akbaş, E. & Atay, A. & Yuksel, I. (2011). The effects of additional kinesio taping over exercise in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Acta orthopaedica et traumatologica turcica. 45. 335-41. 10.3944/AOTT.2011.2403.

- Alshaharani, M. S., Lohman, E. B., Bahjri, K., Harp, T., Alameri, M., Jaber, H., & Daher, N. S. (2019). Comparison of Protonics™ Knee Brace With Sport Cord on Knee Pain and Function in Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 29(5), 547-554.

- Arrebola, L. S., de Carvalho, R. T., Wun, P. Y. L., de Oliveira, P. R., dos Santos, J. F., de Oliveira, V. G. C., & Pinfildi, C. E. (2020). Investigation of different application techniques for Kinesio Taping® with an accompanying exercise protocol for improvement of pain and functionality in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: A pilot study. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 24(1), 47-55.

- Begum, R., Tassadaq, N., Ahmed, S., Qazi, W. A., Javed, S., & Murad, S. (2020). Effects of McConnell taping combined with strengthening exercises of vastus medialis oblique in females with patellofemoral pain syndrome. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 70(4), 728-730.

- Callaghan, M. J., & Selfe, J. (2012). Patellar taping for patellofemoral pain syndrome in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4).

- Clark, D. I., Downing, N., Mitchell, J., Coulson, L., Syzpryt, E. P., & Doherty, M. (2000). Physiotherapy for anterior knee pain: a randomised controlled trial. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 59(9), 700-704.

- Collins, N., Crossley, K., Beller, E., Darnell, R., McPoil, T., & Vicenzino, B. (2008). Foot orthoses and physiotherapy in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome: randomised clinical trial. Bmj, 337, a1735.

- Ghourbanpour, A., Talebi, G. A., Hosseinzadeh, S., Janmohammadi, N., & Taghipour, M. (2018). Effects of patellar taping on knee pain, functional disability, and patellar alignments in patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 22(2), 493-497.

- Günay, E., Sarıkaya, S., Özdolap, Ş., & Büyükuysal, Ç. (2017). Effectiveness of the kinesiotaping in the patellofemoral pain syndrome. Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 63(4), 299.

- Lun, V. M., Wiley, J. P., Meeuwisse, W. H., & Yanagawa, T. L. (2005). Effectiveness of patellar bracing for treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 15(4), 235-240.

- Hossain, M., Alexander, P., Burls, A., & Jobanputra, P. (2011). Foot orthoses for patellofemoral pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1).

- Matthews M, Rathleff MS, Claus A, McPoil T, Nee R, Crossley KM, Kasza J, Vicenzino BT. (2020). Does foot mobility affect the outcome in the management of patellofemoral pain with foot orthoses versus hip exercises? A randomised clinical trial. Br J Sports Med.;54(23):1416-1422.

- Petersen, W., Ellermann, A., Rembitzki, I. V., Scheffler, S., Herbort, M., Brüggemann, G. P.,... & Liebau, C. (2016). Evaluating the potential synergistic benefit of a realignment brace on patients receiving exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery, 136(7), 975-982.

- Smith, T. O., Drew, B. T., Meek, T. H., & Clark, A. B. (2015). Knee orthoses for treating patellofemoral pain syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12).

- Tunay V.B. Baltaci G., Tunay S. & Ergun N. (2003) A comparison of different treatment approaches to patellofemoral pain syndrome. The pain clinic, 15(2) 179-184.

- Uboldi, F. M., Ferrua, P., Tradati, D., Zedde, P., Richards, J., Manunta, A., & Berruto, M. (2018). Use of an elastomeric knee brace in patellofemoral pain syndrome: short-term results. Joints, 6(2), 85.

- Willy RW, Hoglund LT, Barton CJ, Bolgla LA, Scalzitti DA, Logerstedt DS, Lynch AD, Snyder-Mackler L, McDonough CM. (2019) Patellofemoral Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. Sep;49(9):CPG1-CPG95. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2019.0302. PMID: 31475628

- Whittingham, M., Palmer, S., & Macmillan, F. (2004). Effects of taping on pain and function in patellofemoral pain syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 34(9), 504-510.

Evidence tabellen

Evidence table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials and non-randomized observational studies (cohort studies, case-control studies, case series))1

This table is also suitable for diagnostic studies (screening studies) that compare the effectiveness of two or more tests. This only applies if the test is included as part of a test-and-treat strategy - otherwise the evidence table for studies of diagnostic test accuracy should be used.

Research question:

PFP= patellofemoral pain

Notes:

- Prognostic balance between treatment groups is usually guaranteed in randomized studies, but non-randomized (observational) studies require matching of patients between treatment groups (case-control studies) or multivariate adjustment for prognostic factors (confounders) (cohort studies); the evidence table should contain sufficient details on these procedures.

- Provide data per treatment group on the most important prognostic factors(((potential) confounders).

- For case-control studies, provide sufficient detail on the procedure used to match cases and controls.

- For cohort studies, provide sufficient detail on the (multivariate) analyses used to adjust for (potential) confounders.

Evidence table for systematic review of RCTs and observational studies (intervention studies)

Research question:

|

Study reference |

Study characteristics |

Patient characteristics |

Intervention (I) |

Comparison / control (C)

|

Follow-up |

Outcome measures and effect size |

Comments |

|

Taping |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Callaghan, 2012 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to August 2011

A: Clark, 2000 B: Tunay, 2003 C: Whittingham, 2004

Study design: B: RCT, parallel C: RCT, parallel,

Setting and Country: A: UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: SR: University of Manchester, UK; University of Central Lancashire, UK; Department of Health Post-Doctoral Awart, UK; Arthritis Research, UK; no conflicts of interest A: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR: - adults, aged 18 and above, diagnosed with patellofemoral pain.

Exclusion criteria SR: - treatment after patella fracture, dislocation or subluxation EMG (electromyogram) data, gait analysis, patellar position or Alignment studied without pain evaluation

5 studies included (3 relevant for this review)

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N, mean age A: I: 20, Not reported per group B: I: 20, Not reported per group C: age: 18.7 years

Sex: A: not reported per group B: not reported per group C: 80% Male

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: Patellar taping, exercise & education. Tape was applied from the lateral border of the patella pulling medially and upwards over the medial femoral condyle. Taping in this way should reduce pain on the squat test and wall/step down test. If this did not eliminate the pain then the taping was repeated in knee flexion. Type of tape used is not described. B: Patellar taping, ice and home exercises, treatment for 3 weeks C: and one corrective strip of tape. Correction of patellar malalignments of tilt, rotation or glide as identified by the treating physiotherapist.

|

Describe control:

A: Exercise & education (b) footwear and appropriate sporting activities; (c) pain controlling drugs; (d) stress relaxation techniques, ice and massage; (e) diet and weight advice; and (f) prognosis and self-help. Exercise: stretching to the hamstring, iliotibial band, quadriceps and gastrocnemius muscles. Eccentric, isotonic and isometric strengthening exercises to the lower limb B: Ice and home exercises, treatment for 3 weeks C: Exercise programme alone: non–weight-bearing isometric, inner-range isotonic and straight leg raise quadriceps exercises. A variety of weight-bearing exercises (e.g., squats). Stretches for the quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius, and iliotibial band. No home exercise programme.

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 3 months, 12 months B: 3 weeks C: 1,2,3,4 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: "10 patients withdrew from the study and these were included on an intention to treat basis." Participant flow provided. B: not reported C: "All subjects remained in the group to which they were originally assigned."

|

Outcome measure-1: pain VAS, after treatment Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: 0.81 (-0.44, 2.06) B: 0.35 (-0.43, 1.13)

Pooled effect (random effects model: -0.16 (95% CI -1.67 to 1.34) favoring taping Heterogeneity (I2): 91.1%

VAS, 12 months Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: -0.13 (-1.99, 1.73) (favoring taping

Outcome measure-2: function FIQ, end of treatment Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): C: 2.5 (-.82, 3.18) (favoring taping

Cincinnati knee activity score, end of treatment Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: 8.1 (2.93, 13.27) (favoring taping

WOMAC score, end of treatment Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: 1.5 (-6.24, 9.24) (favoring no taping

WOMAC score, 12 months Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: -0.8 (-15.24, 13.64) (favoring taping |

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion: the currently available evidence from trials reporting clinically relevant outcomes is low quality and insuLicientto draw conclusions on the eLects of taping, whether used on its own or as part of a treatment programme.

Risk of Bias due to issues regarding blinding and allocation concealment

|

|

Bracing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Smith, 2015 |

SR and meta-analysis of (RCTs / cohort / case-control studies)

Literature search up to May 2015

A: Evcik, 2010 B: Lun, 2005

Study design: RCT A: RCT, parallel

Setting and Country:

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: (commercial / non-commercial / industrial co-authorship) B: not reported |

Inclusion criteria SR: 'patellofemoral pain', 'anterior knee pain syndrome', 'patellar dysfunction', 'chondromalacia patellae', 'patellar syndrome', 'patellofemoral syndrome' or 'chondropathy'.

Exclusion criteria SR:

5 studies included (2 relevant for this review)

Important patient characteristics at baseline: Number of patients; characteristics important to the research question and/or for statistical adjustment (confounding in cohort studies); for example, age, sex, bmi,...

N, mean age A: I: 41 patients, 42.2 (SD 15.3) yrs B: Ia: 32 patients, 45 knees, 35 (SD11)

Sex: A: I: 15% Male B: not reported

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: knee sleeve + exercise therapy Knee support (Altex Patellar knee support AL-2285C), which is a neoprene sleeve with a patella cut-out. This was worn whilst performing the exercises as well as during the day for the six-week study period. The knee support was only removed at night for sleeping. stabilisation strap to help control patellar movement B-b: exercise and knee sleeve group

|

Describe control:

A: exercise therapy physiotherapist. This consisted of isometric and isotonic programmes for quadriceps muscles, performed five times per week. All participants performed 10 repetitions per day for six weeks. All participants provided with an exercise sheet, outlining the programme. B: exercise group squats. The stretching component of the rehabilitation programme consisted of seated spinal rotations, supine hip external rotation, standing quadriceps stretch, and sitting hamstring stretch. Stretches were performed daily prior to and after the strengthening component of the programme. Each stretch was performed passively 3 times, with each stretch held for 30 seconds

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 6 weeks B: 3, 6 and 12 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: Results section (page 102): "all patients completed the regular exercise program", therefore none appeared lost to follow-up B: Separate participant flow not provided for individual groups. Thus group allocation of the 21 withdrawals and 2 cross-overs excluded from the analyses.

|

Outcome measure-1: pain

Pain during activity 0-10

Knee sleeve: Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: -0.5 (-1.6, 0.6), 6 weeks B: -0.1 (-1.58, 1.38), 12 weeks Pooled effect (fixed effects model), inclusive Miller 1997: -0.48 (95% CI -1.31 to 0.35) favoring sleeve Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Knee brace: Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: -0.2 (-1.68, 1.28), 12 weeks

All braces: -0.46 (95% CI -1.16 to 0.24) favoring brace Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

All braces, B included with number of knee instead of number of patients Ba: -0.2 (-1.43, 1.03), 12 weeks -0.41 (95% CI -1.04 to 0.23) favoring brace Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

Outcome measure-2, function Effect measure: std. mean difference (95% CI): A: -0.08 (-0.5, 0.34), womac Ba: -0.35 (-0.95, 0.24), knee function scale -0.25 (95% CI -0.55 to 0.05) favoring brace Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

functional scores, B included with number of knee instead of number of patients Effect measure: std. mean difference (95% CI): A: -0.08 (-0.5, 0.34), womac Ba: -0.35 (-0.85, 0.14), knee function scale -0.28 (95% CI -0.55 to -0.01) favoring brace Heterogeneity (I2): 0% |

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion: very low quality evidence from clinically heterogeneous trials using different types of knee orthoses (knee brace, sleeve and strap) that using a knee orthosis did not reduce knee pain or improve knee function in the short-term (under three months) in adults who were also undergoing an exercise programme for treating patellofemoral pain.

Risk of bias: regarding allocation, blinding, incomplete outcome data etc.

GRADE regarding VAS: very low (two levels risk of bias, one level downgraded indirectness) |

|

Insoles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hossain, 2011 |

SR and meta-analysis of RCTs

Literature search up to March 2010

A: Collins, 2008 B: Wiener-Ogilvie, 2004

Study design:

Setting and Country: B: single center trial in Winshaw, Lanarkshire, UK

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: SR: Betsy Cadwaladr University health Board, Bangor, UK; University of Oxford, UK; University hospitals of Birmingham, UK; no conflicts of interest A: not reported B: not reported

|

Inclusion criteria SR:

Exclusion criteria SR:

3 studies included (2 relevant for current review)

Important patient characteristics at baseline:

N A: I: 44 B: I: 10

age A: not reported per group B: I: 61.8 years

Sex: A: not reported per group B: not reported per group

Groups comparable at baseline? |

Describe intervention:

A: foot orthoses + physiotherapy: appointment with the physiotherapist if necessary. if necessary, to optimise comfort through heat moulding and by adding wedge or heel raises. The foot orthoses group were prescribed additional home exercise programme. Whereas this was prescribed to be performed bilaterally twice daily. B: foot orthoses + exercises Patients received supervised treatment over a 4 week period. Patients receiving foot orthoses were assessed by the podiatrist once a week for 3 weeks to check for the fitness of the orthoses. Patients were advised to continue to wear the orthoses and perform exercises on their own accord after 4 weeks.

Foot orthoses group were provided with foot orthoses with a 40° rearfoot post. Rearfoot posts and forefoot posts were adjusted using 20° or 40° additional wedges, if necessary.

|

Describe control:

A: physiotherapy of vasti muscle retraining exercises with electromyographic biofeedback, hamstring and anterior hip stretches, hip external rotator retraining, and a home exercise programme.

The participants were advised to continue exercise and activities that did not provoke their pain.

B: exercises week for a further two weeks by a physiotherapist (6 sessions in total). Patients were advised to continue to perform exercises on their own accord after 4 weeks.

• Isometric quadriceps contractions with hip slightly flexed and knee in full extension. • Isotonic quadriceps contractions without resistance. • Isotonic quadriceps contractions with resistance. • Isotonic hamstring contractions. • Dynamic stepping exercise. • Hamstrings stretching exercises. • Isometric hip adductors contractions. • Dynamic side stepping.

|

End-point of follow-up:

A: 6, 12 and 52 weeks B: 8 weeks

For how many participants were no complete outcome data available? (intervention/control) A: I: n=1, lost to follow-up B: I: n=1, drop out

|

Outcome measure-1: pain VAS (worst pain) Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: -3.7 (-12.99, 5.59) (6 weeks) A: -3.4 (-13.52. 6.75) (52 weeks) No pooled effect calculated

F-36 pain scale (change scores at 8 weeks, positive scores = pain reduction) Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): B: 9.6 (-8.99, 28.19)

Knee pain numbers with global improvement) Effect measure: RR (95% CI): 8 weeks B: 1.33 (0.41, 4.33)

Pooled effect (fixed effects model): 1 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.17) Heterogeneity (I2): 0%

52 weeks

Outcome measure-2: function Functional index questionnaire (FIQ) Effect measure: mean difference (95% CI): A: 0.4 (-0.59, 1.39) (6 weeks) A: -0.4 (-1.51, 0.71) (52 weeks) No pooled effect calculated

Knee function: anterior knee pain (Kujala anterior knee pain scale) A: 0.2 (-3.72, 4.12) (6 weeks) A: 3.6 (-0.52, 7.72) (52 weeks) No pooled effect calculated. |

Facultative:

Brief description of author’s conclusion: available evidence does not reveal any clear advantage of foot orthoses over simple insoles or physiotherapy for PFJ pain

Included studies show risk of bias due to issues regarding blinding, selective reporting, similarity at baseline and equal treatment of different groups |

Table of quality assessment for systematic reviews of RCTs and observational studies

Based on AMSTAR checklist (Shea, 2007; BMC Methodol 7: 10; doi:10.1186/1471-2288-7-10) and PRISMA checklist (Moher, 2009; PLoS Med 6: e1000097; doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097)

|

Study

First author, year |

Appropriate and clearly focused question?1

Yes/no/unclear |

Comprehensive and systematic literature search?2

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of included and excluded studies?3

Yes/no/unclear |

Description of relevant characteristics of included studies?4

Yes/no/unclear |

Appropriate adjustment for potential confounders in observational studies?5

Yes/no/unclear/notapplicable |

Assessment of scientific quality of included studies?6

Yes/no/unclear |

Enough similarities between studies to make combining them reasonable?7

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential risk of publication bias taken into account?8

Yes/no/unclear |

Potential conflicts of interest reported?9

Yes/no/unclear |

|

Taping |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Callaghan, 2012 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Bracing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Smith, 2015 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Insoles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hossain, 2011 |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Not applicable |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

- Research question (PICO) and inclusion criteria should be appropriate and predefined.

- Search period and strategy should be described; at least Medline searched; for pharmacological questions at least Medline + EMBASE searched.

- Potentially relevant studies that are excluded at final selection (after reading the full text) should be referenced with reasons.

- Characteristics of individual studies relevant to research question (PICO), including potential confounders, should be reported.

- Results should be adequately controlled for potential confounders by multivariate analysis (not applicable for RCTs).

- Quality of individual studies should be assessed using a quality scoring tool or checklist (Jadad score, Newcastle-Ottawa scale, risk of bias table et cetera).

- Clinical and statistical heterogeneity should be assessed; clinical: enough similarities in patient characteristics, intervention and definition of outcome measure to allow pooling? For pooled data: assessment of statistical heterogeneity using appropriate statistical tests (for example Chi-square, I2)?

- An assessment of publication bias should include a combination of graphical aids (for example funnel plot, other available tests) and/or statistical tests (for example Egger regression test, Hedges-Olken). Note: If no test values or funnel plot included score “no”. Score “yes” if mentions that publication bias could not be assessed because there were fewer than 10 included studies.

- Sources of support (including commercial co-authorship) should be reported in both the systematic review and the included studies. Note: To get a “yes,” source of funding or support must be indicated for the systematic review AND for each of the included studies.

Risk of bias table for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials)

Research question:

|

Study reference

(first author, publication year) |

Describe method of randomisation1 |

Bias due to inadequate concealment of allocation?2

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of participants to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of care providers to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to inadequate blinding of outcome assessors to treatment allocation?3

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to selective outcome reporting on basis of the results?4

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to loss to follow-up?5

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

Bias due to violation of intention to treat analysis?6

(unlikely/likely/unclear) |

|

Taping |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arrebola, 2020 |

Sealed envelops |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

Unclear |

|

Begum, 2020 |

Not reported |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Likely |

|

Ghourbanpour, 2018 |

Not reported |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

|

Gunay, 2017 |

Computerized random numbers |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Akbas, 2011 |

Random number generator |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Unclear |

|

Bracing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alsaharani, 2019 |

Simple randomization |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

Likely |

|

Uboldi, 2018 |

Not reported |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Likely |

Unlikely |

Likely |

|

Petersen, 2016 |

Not reported |

Unclear |

Likely |

Likely |

Unclear |

Unlikely |

Unlikely |

Unclear |

- Randomisation: generation of allocation sequences have to be unpredictable, for example computer generated random-numbers or drawing lots or envelopes. Examples of inadequate procedures are generation of allocation sequences by alternation, according to case record number, date of birth or date of admission.

- Allocation concealment: refers to the protection (blinding) of the randomisation process. Concealment of allocation sequences is adequate if patients and enrolling investigators cannot foresee assignment, for example central randomisation (performed at a site remote from trial location) or sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes. Inadequate procedures are all procedures based on inadequate randomisation procedures or open allocation schedules.

- Blinding: neither the patient nor the care provider (attending physician) knows which patient is getting the special treatment. Blinding is sometimes impossible, for example when comparing surgical with non-surgical treatments. The outcome assessor records the study results. Blinding of those assessing outcomes prevents that the knowledge of patient assignement influences the proces of outcome assessment (detection or information bias). If a study has hard (objective) outcome measures, like death, blinding of outcome assessment is not necessary. If a study has “soft” (subjective) outcome measures, like the assessment of an X-ray, blinding of outcome assessment is necessary.

- Results of all predefined outcome measures should be reported; if the protocol is available, then outcomes in the protocol and published report can be compared; if not, then outcomes listed in the methods section of an article can be compared with those whose results are reported.

- If the percentage of patients lost to follow-up is large, or differs between treatment groups, or the reasons for loss to follow-up differ between treatment groups, bias is likely. If the number of patients lost to follow-up, or the reasons why, are not reported, the risk of bias is unclear.

- Participants included in the analysis are exactly those who were randomized into the trial. If the numbers randomized into each intervention group are not clearly reported, the risk of bias is unclear; an ITT analysis implies that (a) participants are kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they actually received, (b) outcome data are measured on all participants, and (c) all randomized participants are included in the analysis.

Table of excluded studies

|

Author and year |

Reason for exclusion |

|

SRs |

|

|

Barton 2010 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Barton 2014 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Chang 2015 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Collins 2012 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Collins 2018 |

No evidence tables available; references checked |

|

Crossely 2016 |

No evidence tables available; references checked |

|

Eckenrode 2018 |

Does not fit PICO (manual therapy); references checked |

|

Lake 2011 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Logan 2017 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Saltychev 2018 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Swart 2012 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

RCTs after 2017 |

|

|

Aliberti 2019 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Bazett-Jones 2017 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Behrangrad 2020 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Bonacci 2020 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Bonacci 2018 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Bonanno 2018 |

Wrong patientgroup |

|

Collins 2017 |

Wrong patientgroup |

|

dos Santos 2019 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Drew 2017 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Emamvirdi 2019 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Esculier 2018 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

EspÃ-López 2017 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Gaitonde 2019 |

Narrative review |

|

Kolle 2020 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Korakakis 2018 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Matthews 2017 |

Protocol |

|

Matthews 2020 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Melo 2018 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Nielsen 2020 |

No comparison |

|

Priore 2020 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Prohorova 2019 |

Russian |

|

Rathleff 2018 |

No comparison |

|

Selhorst 2020 |

No comparison |

|

Selhorst 2018 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Sutlive 2018 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Talbot 2020 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Wang 2020 |

Wrong patientgroup |

|

Yamamoto 2019 |

Wrong patientgroup |

|

Zahednejad 2017 |

Russian |

|

Zarei 2020 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Additional references (after 2000) from SR |

|

|

Aytar 2011 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Banan Khojaste 2016 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Bolgla 2011 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Campolo 2013 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Collins 2008 |

Similar to Collins 2009 |

|

Crossley 2002 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Denton 2005 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Derassari 2010 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Johnston 2004 |

Wrong design |

|

Kalron 2013 |

Cochrane review available; references checked |

|

Kaya 2010 |

No comparison |

|

Kurt 2016 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Kuru 2012 |

Wrong comparison |

|

Lan 2010 |

No comparison |

|

Lee 2012 |

Wrong design |

|

Lee 2013 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Lewinson 2015 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Mason 2011 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Mills 2012 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Mostamand 2010 |

No comparison |

|

Mostamand 2011 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Osario 2013 |

No combination with exercises |

|

Rathleff 2015 |

Wrong intervention (no taping, braces, insoles) |

|

Syme 2009 |

Wrong comparison |

Verantwoording

Autorisatiedatum en geldigheid

Laatst beoordeeld : 25-01-2022

Laatst geautoriseerd : 25-01-2022

Geplande herbeoordeling : 01-01-2028

|

Module |

Regiehouder(s) |

Jaar van autorisatie |

Eerstvolgende beoordeling actualiteit richtlijn |

Frequentie van beoordeling op actualiteit |

Wie houdt er toezicht op actualiteit |

Relevante factoren voor wijzigingen in aanbeveling |

|

Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen patellofemorale pijn |

VSG |

2022 |

2027 |

1x per 5 jaar |

VSG |

- |

Algemene gegevens

De ontwikkeling/herziening van deze richtlijnmodule werd ondersteund door het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten en werd gefinancierd uit de Stichting Kwaliteitsgelden Medisch Specialisten (SKMS). De financier heeft geen enkele invloed gehad op de inhoud van de richtlijnmodule.

Deze richtlijn is ontwikkeld in samenwerking met:

- Nederlandse Orthopaedische Vereniging

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Radiologie

- Koninklijk Nederlands Genootschap voor Fysiotherapie

- Nederlandse Vereniging van Podotherapeuten

- Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap

- Nederlandse Vereniging voor Arbeids- en Bedrijfsgeneeskunde

De richtlijn is goedgekeurd door:

- Patiëntenfederatie Nederland (en ReumaNederland)

Het Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap heeft een verklaring van geen bezwaar afgegeven.

Samenstelling werkgroep

Voor het ontwikkelen van de richtlijnmodule is in 2019 een multidisciplinaire werkgroep ingesteld, bestaande uit vertegenwoordigers van alle relevante specialismen die betrokken zijn bij de zorg voor patiënten met anterieure kniepijn.

Werkgroep

- Dr. S. van Berkel, sportarts, Isala Zwolle, VSG (voorzitter)

- Dr. M. van Ark, fysiotherapeut, bewegingswetenschapper, Hanzehogeschool Groningen, Peescentrum ECEZG, KNGF

- Drs. G.P.G. Boots, bedrijfsarts, zelfstandig werkzaam, NVAB

- Drs. S. Ilbrink, sportarts, Jessica Gal Sportartsen en Sport- en Beweegkliniek, VSG

- Dr. S. Koëter, orthopedisch chirurg, CWZ, NOV

- Dr. N. Aerts-Lankhorst, waarnemend huisarts, NHG

- Dr. R. van Linschoten, sportarts, zelfstandig werkzaam, VSG

- Bsc. L.M. van Ooijen, (sport)podotherapeut en manueel therapeut, Profysic Sportpodotherapie, NVvP

- MSc. M.J. Ophey, (sport)fysiotherapeut, YsveldFysio, KNGF

- Dr. T.M. Piscaer, Orthopedisch chirurg-traumatoloog, Erasmus MC, NOV

- Drs. M. Vestering, radioloog, Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, NVvR

Met methodologische ondersteuning van

- Drs. Florien Ham, junior adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. Mirre den Ouden - Vierwind, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Dr. Saskia Persoon, adviseur, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

- Drs. Miriam van der Maten, literatuurspecialist, Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten

Belangenverklaringen

De Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling is gevolgd. Alle werkgroepleden hebben schriftelijk verklaard of zij in de laatste drie jaar directe financiële belangen (betrekking bij een commercieel bedrijf, persoonlijke financiële belangen, onderzoeksfinanciering) of indirecte belangen (persoonlijke relaties, reputatiemanagement) hebben gehad. Gedurende de ontwikkeling of herziening van een module worden wijzigingen in belangen aan de voorzitter doorgegeven. De belangenverklaring wordt opnieuw bevestigd tijdens de commentaarfase.

Een overzicht van de belangen van werkgroepleden en het oordeel over het omgaan met eventuele belangen vindt u in onderstaande tabel. De ondertekende belangenverklaringen zijn op te vragen bij het secretariaat van het Kennisinstituut van de Federatie Medisch Specialisten.

|

Werkgroeplid |

Functie |

Nevenfuncties |

Gemelde belangen |

Ondernomen actie |

|

Ilbrink |

Sportarts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Ooijen |

Sportpodotherapeut bij Profysic Sportpodotherapie |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Linschoten |

Sportarts, zelfstandig werkzaam |

Hoofdredacteur Sport&Geneeskunde |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Piscaer |

Orthopedisch chirurg-traumatoloog, ErasmusMC |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Boots |

Bedrijfsarts, zelfstandig werkend voor Stichting Volandis (het kennis- en adviescentrum voor duurzame inzetbaarheid in de Bouw & Infra) en de arbodiensten Human Capital Care en Bedrijfsartsen5. |

Sportkeuringen bij Stichting SMA Gorinchem (betaald), commissie medische zaken "Dordtse Reddingsbrigade" (onbetaald) en |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Vestering |

Radioloog Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Van Ark |

Docent - Hanzehogeschool Groningen opleiding fysiotherapie |

Bij- en nascholing op het thema peesblessures voor verschillende organisaties (betaald) |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Ophey |

In deeltijd als fysiotherapeut werkzaam bij 1e lijns praktijk voor fysiotherapie "YsveldFysio" in Nijmegen, https://www.ysveldfysio.nl/ |

Bij- en nascholing van fysiotherapeuten voor verschillende organisaties in binnen-en buitenland), waarbij een enkele scholingsdag ook betrekking heeft op het thema "patellofemorale pijn". (betaald; gastdocent). |

Wetenschappelijk onderzoek gericht op mobiliteit in de kinetische keten bij patiënten met patellofemorale pijn (risicofactor) en op homeostase verstoringen in het strekapparaat (niet gesubsidieerd). |

Geen actie |

|

Van Berkel* |

Sportarts, Isala Zwolle |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Aerts - Lankhorst |

Waarnemend huisarts |

Geen |

Geen |

Geen actie |

|

Koëter |

Orthopaedisch chirurg CWZ |

Deelopleider Sportgeneeskunde CWZ Hoofd research support office CWZ |

Geen |

Geen actie |

Inbreng patiëntenperspectief

Er werd aandacht besteed aan het patiëntenperspectief door een vragenlijst uit te zetten onder patiënten. De respons op de vragenlijst is besproken in de werkgroep en de verkregen input is meegenomen bij het opstellen van de overwegingen (zie waarden en voorkeuren voor patiënten). De conceptrichtlijn is tevens voor commentaar voorgelegd aan de Patiëntenfederatie Nederland en de eventueel aangeleverde commentaren zijn bekeken en verwerkt.

Kwalitatieve raming van mogelijke financiële gevolgen in het kader van de Wkkgz

Bij de richtlijn is conform de Wet kwaliteit, klachten en geschillen zorg (Wkkgz) een kwalitatieve raming uitgevoerd of de aanbevelingen mogelijk leiden tot substantiële financiële gevolgen. Bij het uitvoeren van deze beoordeling zijn richtlijnmodules op verschillende domeinen getoetst (zie het stroomschema op de Richtlijnendatabase).

Uit de kwalitatieve raming blijkt dat er waarschijnlijk geen substantiële financiële gevolgen zijn, zie onderstaande tabel.

|

Module |

Uitkomst raming |

Toelichting |

|

Module Anamnese en lichamelijk onderzoek PT |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Oefentherapie Patellofemorale pijn (PFP) |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen PFP |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Medicamenteuze behandelingen bij PFP |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Open chirurgie PT en PFP |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Oefentherapie patella tendinopathie (PT) |

geen financiële gevolgen |

Hoewel uit de toetsing volgt dat de aanbeveling(en) breed toepasbaar zijn (5.000-40.000 patiënten), volgt ook uit de toetsing het geen nieuwe manier van zorgverlening of andere organisatie van zorgverlening betreft. Er worden daarom geen substantiële financiële gevolgen verwacht. |

|

Module Aanvullende conservatieve behandelingen PT |

geen financiële gevolgen |